‘Undeniably groundbreaking’ work shows that declining egg quality in older mice can be reversed with a dietary supplement.

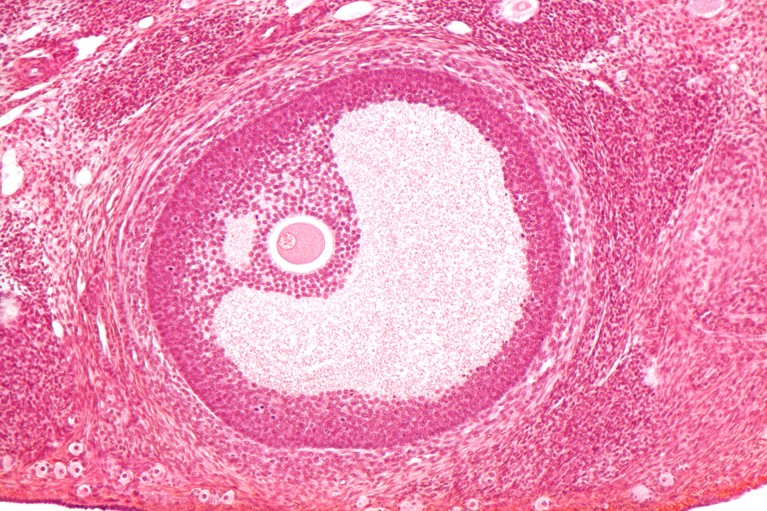

Follicles — the structures that hold developing egg cells — degenerate with age. Credit: M. I. Walker/Science Photo Library

Declining fertility in older mice has been reversed by giving the animals a compound already found in most living cells. The process also causes them to produce larger litters. The findings, published today in Nature Aging1, offer clues that could aid the development of treatments for humans with fertility issues.

The chances of falling pregnant — naturally or with assistive technology such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) — become slimmer with age. This can be traced to reproductive cells in the ovaries called oocytes, which deteriorate and decrease in number throughout life.

A molecule called spermidine — first isolated from sperm but now known to have functions in many types of cell — has been shown to lengthen lifespan in yeast, flies, worms and human immune cells. Increased dietary intake of spermidine has also been linked with reduction of age-related problems in laboratory animals, including cardiovascular disease in mice and cognitive decline in fruit flies. But its effects on ageing oocytes were unclear.

The latest study uncovers the molecule’s potential to address major hurdles in reproductive medicine, says Alex Polyakov, a fertility specialist at the University of Melbourne in Australia. “This research is undeniably groundbreaking.”

For the study, Bo Xiong, a reproductive biologist at Nanjing Agricultural University in China, and his colleagues compared ovarian tissue samples from young and middle-aged mice and found that the older mice had much less spermidine in their ovaries. The older mice also had poorer-quality oocytes and more degenerated follicles, structures in the ovaries that hold oocytes and release them during ovulation.

Exploring whether these observations were linked, the researchers injected some of the older mice with spermidine and compared their oocytes to those of control mice. The oocytes in spermidine-boosted mice developed more quickly and had fewer defects than those in the untreated ageing mice.

Mice given the supplement also had more follicles, a measure often used in humans to estimate the number and quality of oocytes. This suggested the spermidine slowed the degeneration of follicles with age. Even when the researchers delivered spermidine in drinking water instead of with an injection, it still reversed signs of oocyte ageing.

The spermidine boost also improved the success rate of the formation of blastocysts, the fertilized balls of dividing cells that develop into embryos. And ageing mice that received the compound and then conceived naturally produced roughly twice as many young per litter as did the control ageing mice.

Xiong and his team then investigated the mechanism behind spermidine’s effects. Noting that oocytes from untreated mice didn’t clear away damaged mitochondria — the energy-producing components in cells — as efficiently as did younger oocytes, they sequenced the cells’ RNA. They found that genes linked to cell energy production and processes that clean up cellular debris had different expression patterns in young mice, older mice and older mice that had received spermidine.

In spermidine-enriched mice, oocytes recovered their ability to clear out broken components. The compound also seemed to enhance the function of healthy mitochondria in ageing mice. The effect was similar in aged pig oocytes in a laboratory dish that were put under stress, hinting that spermidine’s mechanism of action could be consistent across species. “Although we have known about the anti-ageing properties of spermidine, we were still surprised by its remarkable effects,” says Xiong.

When the researchers treated lab-cultured oocytes with a molecule that inhibits the mitochondria-clearing process, they found that the spermidine-dosed cells matured much slower than those that weren’t treated with anything at all, further suggesting that the compound works with the cellular clean-up process to deliver its anti-ageing effects.

The results hint that spermidine could be a promising fertility enhancer, says Xiaopeng Hu, a reproductive biologist at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China. But before it lands in clinics, researchers need to investigate its safety, side effects and how various doses affect other processes in the body, such as cell and organ function, he says.

Jeremy Thompson, a reproductive biologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia, agrees. “The real proof will be when it reaches well-designed and conducted clinical trials.”

The next step for Xiong and his team is to test spermidine’s fertility-enhancing potential on human oocytes in the lab, investigating safe and effective doses. Getting the dose right is important, as the study also showed that excessive amounts of spermidine led to poorer quality oocytes in mice. "We need precise clinical trials to address these concerns before spermidine can be applied to boost fertility in humans," he says.