Researchers disagree over how bad it is to be reinfected, and whether COVID-19 can cause lasting changes to the immune system.

People crowd onto a ferry boat in Toronto, Canada, in July 2022, as the Omicron variant prompted a surge in cases.Credit: Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto via Getty

When the coronavirus pandemic began in early 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus was a strange and terrifying adversary that plunged the world into chaos. More than three years later, the infection’s symptoms are all too familiar and COVID-19 is here to stay — part of a long list of common diseases that infect humans. Experts estimate that the majority of the world’s population has been infected at least once; in the United States, some estimates suggest that as many as 65% of people have had multiple infections1. And it’s likely that in the decades to come, we’re all destined to get COVID-19 many more times.

Just how much harm repeat infections will cause is a matter of debate. “There are some almost pathologically polarized opinions out there,” says Danny Altmann, an immunologist at Imperial College London. One side argues that SARS-CoV-2 is a run-of-the-mill respiratory virus, no worse than the common cold, especially for those who have been vaccinated. Others have said that repeatedly getting COVID-19 is a gamble. Each bout comes with a risk of damage — or at least changes — to the immune system, and long-term health repercussions. Both groups are armed with evidence. What do the data say about the risks of reinfection and the potential for COVID-19 to cause lasting consequences?

First, reinfection so far seems to be relatively rare in studies that tested people for the virus over time. The latest data from various countries suggest rates ranging from 5%2 to 15%3, although this proportion is expected to increase as time passes.

When reinfection does occur, the good news is that the immune system seems primed to respond. In a preprint posted in March4, researchers examined reinfections in US National Basketball Association players, staff and their families. They found that people who became reinfected cleared the virus faster — in about five days, on average, compared with about seven days for a first infection. People who had a vaccine dose between their first and second infection cleared the virus the fastest, says Stephen Kissler, an infectious-disease researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the paper.

Other studies have shown that people who experience mild symptoms with their first infection will probably have a mild subsequent infection5. And two large studies suggest that reinfections tend to be less risky than the initial one. In one study6, researchers compared two groups of unvaccinated people in Qatar — around 6,000 who had been infected once and 1,300 who had been reinfected. The odds of severe, critical or fatal disease at reinfection were almost 90% lower than that for a primary infection.

How quickly does COVID immunity fade? What scientists know

The other study7, which looked at 3.8 million first infections and 14,000 reinfections in England, found that people were 61% less likely to die in the month following reinfection than in the same period after a first infection, and 76% less likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit.

But reinfection isn’t risk free. Those who are most vulnerable to severe disease during a first infection continue to be the most vulnerable, even if their risk of hospitalization or dying diminishes. In a January preprint5, researchers analysed data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative in the United States, which contains clinical information on more than 16 million people. The vast majority of those who got reinfected — more than three-quarters — had a mild illness both times. A small proportion of people who weren’t hospitalized the first time did end up in the hospital on reinfection. But a severe second infection was much more common in people who had a severe first infection. Of the people who had to be put on a ventilator during their first infection, 30% ended up back in the hospital on reinfection. “They should have some degree of concern,” says Richard Moffitt, a biostatistician at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

One reinfection paper that garnered a lot of media attention looked at electronic health records from the US Department of Veterans Affairs8. In the database, the researchers found nearly 500,000 people who were infected by SARS-CoV-2 once, and about 41,000 who had 2 or more confirmed infections. The paper did not compare the severity of first and subsequent infections. Instead, the researchers compared the outcomes of people infected once with those who had two or more infections. At the time, Ziyad Al-Aly, an epidemiologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, was seeing people who had been both vaccinated and infected. They felt bulletproof. “People in the press started referring to these patients as ‘super immune’.” Al-Aly wanted to know if a second infection would even matter for those individuals.

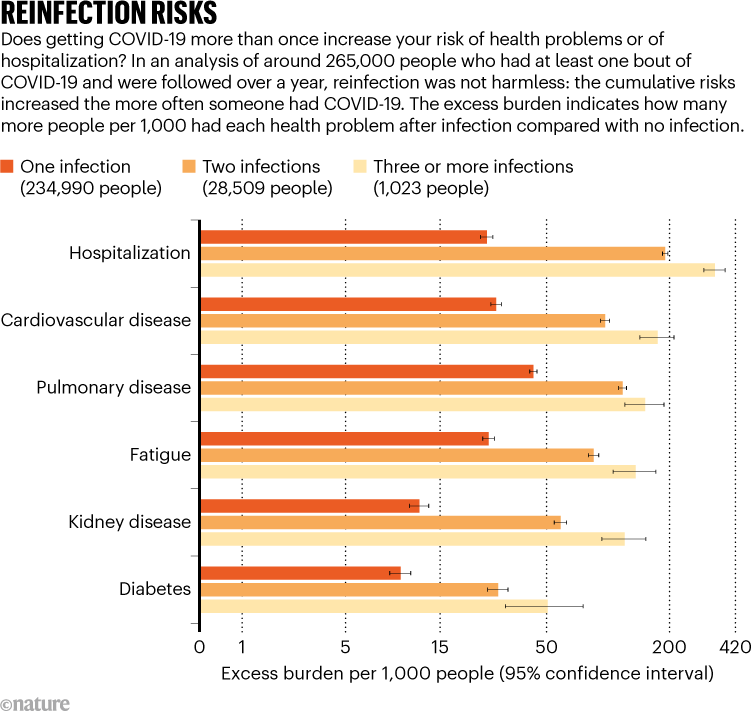

The study showed that it did (see ‘Reinfection risks’). Having COVID-19 more than once is worse than having it just once. “It’s not really surprising,” Al-Aly says. If you get hit in the head twice, he says, it will be worse than one blow. People with repeat infections were twice as likely to die and three times as likely to be hospitalized, have heart problems or experience blood clots than were people who infected only once. In a surprising twist, vaccination status didn’t seem to have an impact — although other studies show vaccines to be protective. Whether these results hold true for the general population is up for debate. The Veterans Affairs cohort was made up mostly of older white men, which is not representative of the wider population.

Source: Ref. 8

It might be impossible to avoid infection altogether, says Preeti Malani, an infectious-disease physician at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. But, she adds, “getting COVID a second or third time isn’t good for anyone.”

That every new bout of COVID-19 carries some risk wasn’t a shock to Al-Aly. What did come as a revelation is that the risks associated with reinfection extend beyond the acute phase. Even six months after reinfection, the researchers found an excess risk of outcomes such as heart disease, lung problems, diabetes, fatigue, neurological disorders. “If you dodged the bullet that first time and did not get long COVID, upon reinfection you could still get long COVID,” Al-Aly says.

The latest data (go.nature.com/3h6vl67) from the UK Office of National Statistics, however, suggest that the risk of long COVID diminishes with subsequent infections. Adults had a 4% risk of developing long COVID after a first infection, and that declined to 2.4% after reinfection. For children and young people, the long-COVID risk after a first infection was 1% and didn’t decline much.

For people who already have long COVID, reinfection seems to exacerbate symptoms. In a survey of nearly 600 people with long COVID (go.nature.com/3a0aadc), conducted by the charity Long Covid Kids & Friends, based in Salisbury, UK, 80% reported that reinfection worsened at least some of their symptoms. Only 15% reported that reinfection had no impact on symptoms.

There’s another reason why some scientists think that a SARS-CoV-2 infection — whether first or fourth — is worth avoiding. Some argue that even mild cases of COVID-19 can cause lasting damage to the immune system, which could make people more susceptible to other kinds of infection. This has been floated as an explanation for the surge in cases of influenza and other respiratory illnesses in the Northern Hemisphere beginning in October last year. Such evidence “dispels the myth that repeated brushes with the virus are mild and you don’t have to worry about it”, says Rambod Rouhbakhsh, a physician at the Forrest General Hospital in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in a press release. “It is akin to playing Russian roulette.”

Many immunologists, however, say that evidence for that hypothesis is lacking. Immune abnormalities do seem to accompany long COVID and linger after severe cases of COVID-19, but for most people who have recovered, there is no sign that the virus causes a long-lasting immune deficiency. “We know what immunodeficiency really looks like,” says Sheena Cruickshank, an immunologist at the University of Manchester, UK. Only a few common viruses have the ability to suppress the immune system: HIV infects and destroys immune cells such as T cells, leaving people more vulnerable to other types of infection; measles infects immune memory cells, making them targets for destruction and prompting the immune system to forget pathogens it has previously met.

People walk past a COVID-19 testing site in New York in June 2022. Estimates suggest most people in the United States have had COVID-19 multiple times.Credit: Stephen Shaver/Shutterstock

Nonetheless, a handful of studies have found immunological changes that last weeks or even months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection — even in people who had a mild illness and seem to have fully recovered. Several studies have looked at different immune markers, such as inflammatory proteins and various immune cells, and have observed changes that linger.

A paper published earlier this year that raised concerns compared the T cells of people in three groups: those who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 but never vaccinated, those who were vaccinated but never infected and those who were infected and then vaccinated9. The researchers observed marked differences in the number and activity of killer T cells, which seek out and destroy infected cells. In the group that was infected then vaccinated, the vaccine prompted a weaker killer-T-cell response than it did in the group that had been vaccinated but never infected. The fainter response is “cause for concern”, the authors write, because it might mean that people are vulnerable to repeat infections or other health issues even if they have been vaccinated.

But the significance of any of the changes seen so far isn’t entirely clear. “We don’t know how they read out in terms of people’s lives,” Altmann says.

Marc Veldhoen, an immunologist at the University of Lisbon, bristles at the description of these changes as immune dysfunction or dysregulation. Much of what these papers describe is the tail end of a normal physiological response to a new infection, he says. Roughly speaking, SARS-CoV-2 “behaves like all the other viruses we are familiar with”, he says. “We haven’t discovered something magical about this virus.”

Some papers that find no immune dysfunction have been taken as evidence that it does in fact exist. Margarita Dominguez-Villar, an immunologist at Imperial College London, and her colleagues published a study10 showing that monocytes — a type of immune cell that serves as a first line of defence against pathogens — express genes linked to clot formation after a SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study looked only at acute infection, and didn’t show evidence of immune damage. But on Twitter, the research took on a life of its own; some tweets claimed it showed a rewiring of innate immunity. “Suddenly I see my paper being retweeted like 1,000 times,” she says. “I think it generated a lot of panic when there shouldn’t be any.”

It’s hard to say. No other virus has been the focus of such intense study using the full arsenal of modern tools available to researchers. Many of the immunological changes being observed might be present after other viral infections, says Dominguez-Villar. “If we were to look at, for example, influenza, as deeply as we have been looking at COVID, we will probably find some similarities.”

One coronavirus infection wards off another — but only if it’s a similar variant

Perhaps scientists have been wrong to assume that infection with any virus is followed by a return to the baseline. In one small study published in January11, researchers assessed this by looking at whether COVID-19 changes the immune system. The researchers recruited 33 people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 early in the pandemic and took blood samples for several months, before and after they got their flu shots. When they compared those individuals to people who had their flu shot without having had COVID-19, they found differences that they weren’t expecting between male and female participants. Typically, the female response to a flu vaccination is stronger. “In this case, we saw the flip,” says John Tsang, a systems immunologist at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, who co-authored the study while in his post at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

“It may not be that we’ve made things better or worse, we’ve just made it a little bit different,” says John Wherry, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. His own investigations of the immunological aftermath of SARS-CoV-2 haven’t revealed any significant changes. In a February preprint12, his team looked at the immune response in vaccinated people who later became infected. “We see markers of high T-cell activation, high B-cell activation. That all returned to baseline levels within 45–60 days,” he says.

Many of these questions might never be fully answered. Even as reinfections become more common, they have become harder to track as testing for COVID-19 has dropped off. Furthermore, the landscape of COVID-19 immunity is becoming increasingly complex. People vary by the number and type of vaccine doses they’ve received, whether they’ve been infected and with what variant and the timing of each exposure. “It’s not clean to look at those things,” Tsang says.

Whatever the risks, COVID-19 is here to stay — still evolving, still infecting and reinfecting people and likely to keep on revealing secrets of the immune system.