Report also supports projects of unprecedented scale to study dark matter, neutrinos and the Higgs boson.

The Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. The next major collider is a major focus for particle physicists.Credit: Valentin Flauraud/AFP via Getty

The United States should fund proposed projects to dramatically scale up its efforts in five areas of high-energy physics, an influential panel of scientists has concluded.

Topping the ranking is the Cosmic Microwave Background–Stage 4 project, or CMB-S4, which is envisioned as an array of 12 radio telescopes split between Chile’s Atacama Desert and the South Pole. It is designed to look for indirect evidence of physical processes in the instants after the Big Bang — processes that have been mostly speculative so far.

The other four priorities are experiments to study the elementary particles called neutrinos, both coming from space and made in the laboratory; the largest-ever dark-matter detector; and strong US participation in a future overseas particle collider to study the Higgs boson.

Particle physicists want to build the world’s first muon collider

An ad hoc group called the Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel (P5) presented the recommendations on 7 December. The committee, which is convened roughly once a decade, was charged to make recommendations for the two main US agencies that fund research in high-energy physics, the Department of Energy (DoE) and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

In addition to the five key recommendations, the report says that the United States should embark on a programme to demonstrate the feasibility of two completely new kinds of particle accelerator, after a surge of grass-roots enthusiasm in the particle-physics community.

The P5 also endorsed smaller-scale projects. But its strongest recommendation is for uninterrupted US funding of experiments that are either ongoing or under construction. These include the first major upgrade of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which will keep the collider — at CERN, Europe’s high-energy physics lab near Geneva, Switzerland — going throughout the 2030s.

The P5’s priorities were selected from proposals presented by the broader research community at the Snowmass conference last year in Seattle, Washington. These were balanced against realistic funding levels, says Hitoshi Murayama, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, who chaired the P5 committee.

Before any large new projects can begin, they must be approved by the DoE or the NSF, and then must win funding from Congress and, in some cases, other governments. But historically, the consensus-forming nature of the P5 process has added credibility to the community’s requests, and has helped most of the projects prioritized by previous panels to come to fruition.

Nature explores the P5 report’s five leading proposals, ranked in order of importance, as well the panel’s discussion of future accelerators.

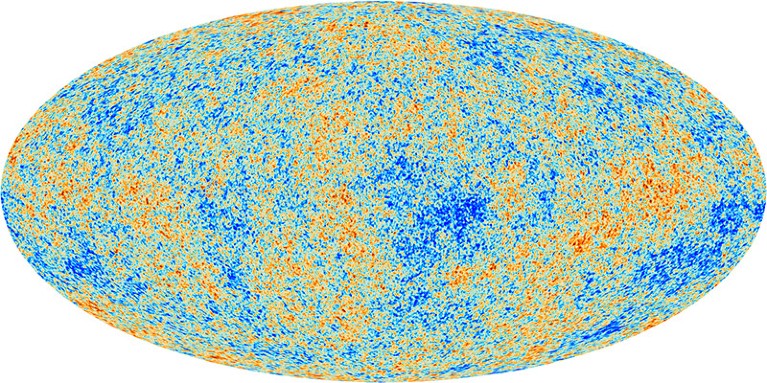

Studying the cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the lead priority of the US particle-physics community.Credit: ESA and the Planck Collaboration

The goal of CMB-S4 is to study radiation that was created around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the nearly uniform broth of particles in the Universe transitioned from plasma to gas. Microwave antennas will measure the cosmic microwave background’s (CMB’s) polarization — the angle at which most of the radiation’s electric fields wiggle as they reach Earth — across a large portion of the sky. Physicists hope that the resulting polarization map will reveal a signature pattern created by gravitational waves that have been shaking the fabric of space-time since the first instant after the Big Bang. The CMB is the oldest electromagnetic radiation that can be detected, but its polarization could provide a window into much earlier times.

Multiple large experiments have attempted to find signs of primordial gravitational waves in the CMB polarization, including the European space telescope Planck and the BICEP2 telescope at the South Pole. In the Atacama Desert, astronomers are building an array of dishes called the Simons Observatory, due to be completed in mid-2024. Researchers envisage CMB-S4 as a scaled-up version of the Simons Observatory that would begin observations in the mid-2030s.

An underground test blast area for the DUNE neutrino experiment at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota.Credit: Reidar Hahn/Fermilab

The Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) is already under construction and is expected to be completed in the early 2030s. But the P5 is already pushing for it to be expanded.

DUNE will involve two sites: the DoE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) outside Chicago, Illinois, and the Sanford Underground Research Facility in Lead, South Dakota. An accelerator at Fermilab will create a beam of neutrinos and shoot it in a straight line through Earth’s crust, from which it will re-emerge nearly 1,300 kilometres away.

The previous P5 prioritization exercise, which took place in 2014, put DUNE — then estimated to cost US$1.9 billion — at the top of its priorities for new projects to fund. Construction has since been subject to major delays and cost overruns, which has prompted the DoE to nearly halve the size of the South Dakota detector. Even in this scaled-down version, the project is expected to exceed $3 billion.

But the science case for DUNE remains extremely compelling, many physicists think. The P5 is now advocating a second phase that will push the detector to its original intended size, and include upgrades at Fermilab that will make its neutrino beam ten times more intense.

A ProtoDUNE neutrino detector, one of two testbeds for the Fermilab-hosted experiment.Credit: Jim Shultz/Fermilab

The LHC announced the discovery of the Higgs boson — which is thought to give other particles their mass — in 2012. It was the last particle to be found among those predicted by the standard model of particle physics. But in many respects, the Higgs remains mysterious.

Physicists have proposed several designs for accelerators that would produce vast numbers of Higgs bosons and enable precise measurements of their interactions with other particles. These studies could point to possible changes to the standard model, or even to a completely new theory that will supersede it.

There are two leading proposals for a Higgs factory. One is the International Linear Collider, which would probably be led by and sited in Japan. The other is a circular collider around 90 kilometres long that CERN hopes to build next to the LHC (a detailed feasibility study is under way). Both these projects can be carried out with current technology, says the P5 report, and if either of them is built, the United States should make a significant contribution to it, as it did to the LHC. (China is developing its own design for a large-scale circular Higgs factory.)

Many experiments have attempted to detect winds of dark matter sweeping through the Solar System, but to no avail so far. The idea is that hypothetical weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) might occasionally collide with atoms in a detector and release telltale flashes of energy.

The P5 report says this search should be taken to its ultimate conclusion with a scaled-up detector, and that the US agencies should fund an attempt.

One approach to WIMP detection, using liquid xenon, has become the strongest contender as researchers have built detectors with larger and larger amounts of xenon, now approaching 10 tonnes. These have excluded a wide range of particle interactions in a bid to see WIMPs, but researchers say that fully exploring the possibilities will require 50 tonnes.

Any more sensitive, and such experiments will begin to suffer from interference caused by neutrinos, Murayama told Nature. “In some sense, that’s the ultimate experiment, because once neutrinos become a problem, then we really have to start to think what’s next.”

IceCube is an observatory that detects showers of particles streaming through the 3-kilometre-deep ice sheet at the South Pole each time a high-energy neutrino collides with an atom in the ice or in the underlying crust. Sensitive detectors pick up flashes of light produced by the particles travelling through 1 km3 of ice.

IceCube has scored a number of discoveries. Among them are the first ultrahigh-energy neutrinos, the first neutrino traced to a distant source and the first neutrino map of the Milky Way.

The P5 report endorses IceCube-Gen2. This will involve monitoring a tenfold bigger volume of ice — around 10 km3 — with a comparable increase in the number of neutrinos researchers can catch. The $350-million upgrade would advance multiple themes in neutrino research and could unequivocally identify the sources of the most energetic particles.

The panel proposed exploration of a collider that would smash together muons, particles similar to electrons but 207 times more massive. Physicists say it is still unclear whether such a machine can be built, but the panel recommends scaling up research and development with the aim of building a proof-of-principle collider.

“We don’t know if a muon collider is possible, but working towards it comes with high rewards,” said Murayama at the press conference announcing the report.

Agencies should also boost research on technology that accelerates electrons using plasma, and on advanced magnets for more conventional colliders. “We’re not abandoning anything at this stage, but would like to have all these three options taken seriously,”