Researchers say the Norwegian government ignored warnings of potential ecosystem harm.

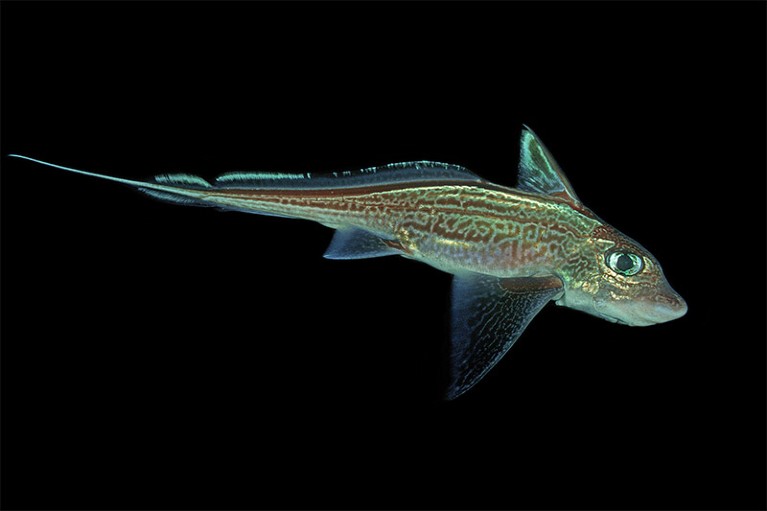

Deep-water species such as the rabbit fish (Chimaera monstrosa) are likely to be affected by sea-bed mining.Credit: SeaTops/Alamy

The controversial practice of extracting valuable minerals from the sea bed has taken a step forward after Norway became the first country to allow exploratory deep-sea mining — disappointing scientists and environmental organizations who say that the method will irreversibly damage biodiversity and ecosystems.

Seabed mining is coming — bringing mineral riches and fears of epic extinctions

“This is about greed, not need, and will come at a significant cost to our environment for present and future generations,” says Matthew Gianni, co-founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an advocacy group in Amsterdam.

On 9 January, Norway’s parliament voted 80–20 in favour of allowing exploratory mining on the continental shelf in the Norwegian Sea. The aim is to map the sea bed in the country’s jurisdiction and investigate whether sulfides and manganese crusts — currently mined on land — could be extracted profitably from the sea floor.

The Norwegian government, which has been pursuing its mining plan since 2020, says that sea-bed extraction is necessary to secure supplies of metals such as manganese and cobalt, which are used in the manufacturing of electric-vehicle batteries and other electronics intended to help the transition to a low-carbon economy. But many scientists and organizations including the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council — a Brussels-based group of national science academies — say that this claim is misleading, and argue that terrestrial mineral resources are sufficient.

Although research on the ecological impacts of deep-sea mining is limited, studies are beginning to show that it could harm species on the sea bed by crushing them with machinery or smothering them with plumes of sediment that are kicked up by mining activities. Species in the water column, such as jellyfish, are also at risk1. Many researchers and governments are calling for a moratorium on sea-bed mining until more is known about deep-sea ecosystems.

Norway’s decision means that the government can issue permits to let companies and other entities explore a reported 281,000 square kilometres of the sea bed. Permission to extract minerals for commercial activities will require a further parliamentary vote, but many scientists and environmental organizations see this week’s result as a gateway to that goal.

Norwegian scientists say they are disappointed but not surprised by the move. They say that the government ignored their scientific advice and that of the nation’s environment agency in Trondheim. In response to a public consultation on the government’s mining plans, scientists said that too little is known about the biodiversity and ecosystem functions of the proposed sites to enable mining to go ahead safely.

“How can we make meaningful judgements of acceptable harm or risk when we know absolutely nothing about it?” says Peter Haugan, director of policy at the Institute of Marine Research in Bergen.

Helena Hauss, a marine ecologist at NORCE, an independent research institute with headquarters in Bergen, says that the proposed mining sites are inhabited by communities not found elsewhere, and will be irreversibly damaged. “This is difficult to align with the claim of the Norwegian government that this will be done in a sustainable and responsible way,” she says.

Haugan says that Norway’s decision could be illegal under national law, because the government lacked sufficient scientific evidence to assess the impacts of future mining activities. He anticipates that environmental groups will launch lawsuits on these grounds to try to stop mining going ahead.

He is also concerned that the government will ignore scientific advice when requests for commercial exploitation are considered. The government suggests that exploitation is around 20 years away, but environmental organizations say it could happen sooner.

Gianni says companies that finance exploration of the sea bed are likely to want commercial licences in return for their investments.

Internationally, negotiations continue on whether to permit commercial harvesting of the sea floor in mineral-rich areas outside national jurisdictions. One disputed site is the Clarion–Clipperton Zone, a 4.5-million-square-kilometre area in the eastern Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico. Norway is among the strongest proponents of deep-sea mining in international discussions, says Gianni.