UK researchers can once again access the €95-billion funding programme — for some, the deal has come too late.

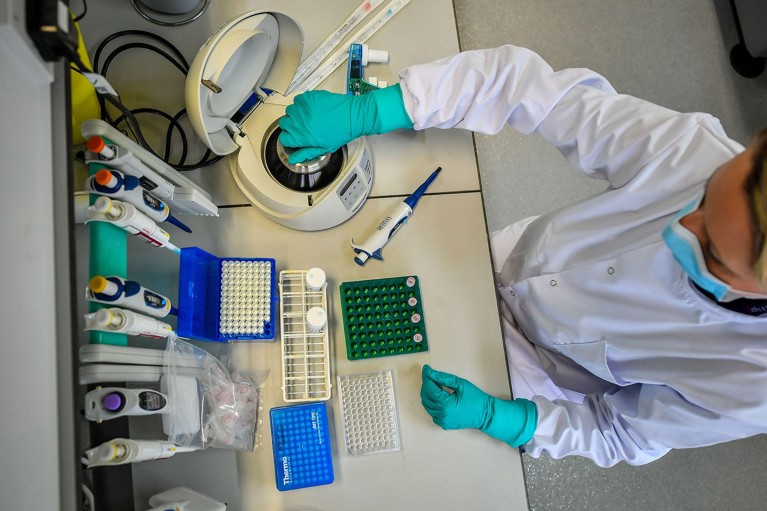

British scientists have been frozen out of the European Union’s flagship research-funding programme for two years. Credit: Ben Birchall/PA via Alamy

On 7 September, scientists celebrated the news that the United Kingdom will rejoin the European Union’s €95-billion (US$102-billion) Horizon Europe research-funding programme, after two anxiety-filled years of political negotiation.

Scientists celebrate as UK rejoins Horizon Europe research programme

But the turmoil has taken a toll on some scientists. After the post-Brexit transition period ended in 2021, UK researchers were unable to access Horizon grants owing to political disagreements over part of the Brexit deal — which defines the United Kingdom and EU’s relationship after Brexit — relating to trade in Northern Ireland. Many scientists, including those who won prestigious European Research Council (ERC) grants at the beginning of Horizon Europe’s term, were faced with either giving up their funding or moving to an EU institution so they could participate in the scheme.

The ERC provides funding for basic research that can be challenging to secure from UK agencies, says Christoph Treiber, a neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, UK, who gave up an ERC grant. “For some of the medical research money, that sort of basic research is just not funded.”

Nature spoke to scientists about how the disruption has affected their life and work, and how they feel about the United Kingdom rejoining Horizon Europe.

Mortiz Treeck moved from the United Kingdom to Portugal to keep his ERC grant funding.Credit: Moritz Treeck

Moritz Treeck, parasitologist at the Gulbenkian Science Institute, Oeiras, Portugal

In December 2021, while working at the Francis Crick Institute in London, I was awarded an ERC grant of €2 million over five years to research human and livestock parasites. Shortly after, I was told that I couldn’t take the grant in the United Kingdom because the country was no longer associated with Horizon Europe. I was given a choice: move to an EU state or accept replacement funding from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), which was running a guarantee scheme for researchers in my situation. That was a life decision — not only for me, but for my family and the people in my laboratory. I had to think about my children’s education, work permits and my colleagues’ careers.

How European scientists will spend €100 billion

One deciding factor was that the ERC grants allow you to move across borders and follow where you want to do the science, whereas UKRI funding restricts you to the United Kingdom. Because of the limited term of my employment, staying put would have meant hiring more people in the middle of the grant period and firing them again after only a few years. I wasn’t willing to do that.

I decided to accept the ERC grant and move to Portugal with five scientists from my team to do my project. I’m setting up ahead of their arrival next week. Although everything is going well, I know that the move was more stressful for everyone than if they just stayed in the United Kingdom.

Rejoining Horizon Europe is a really good thing for science, and I’m really happy for my UK colleagues and those who can access EU funding again. But the way that it was communicated as a win for the United Kingdom fundamentally goes against what Horizon is about: collaboration across borders. It’s a success for science, not just for the country.

Jordana Bell had to reject a €2 million ERC grant.Credit: King's College London

Jordana Bell, geneticist at King’s College London

In January, I was awarded a €2-million ERC grant to study bacterial methylation in the human gut and how it relates to health. The ERC said that if I wanted to keep the grant, I had to move to an EU country. In my situation — having a family with young children — that wasn’t really feasible, at least for the next few years.

I decided to wait until the last possible moment to see how the political situation would develop. At one point it looked very positive. But the decision date came, and there was only one choice left. I had to decline the grant. I ended up applying to the UKRI guarantee scheme, and the project will start in January 2024.

Formally, I rejected the grant. So I won’t be an ERC grant holder, which might affect my future recruitment or collaborations. But it’s difficult to measure. The research still carries on and that’s the important thing.

Chris Drakeley says UK researchers have missed out on collaborations while unable to access EU funding.Credit: Tanya Marchant

Chris Drakeley, immunologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

In February 2022, my group was awarded an €8-million Horizon 2020 grant over five years to test a novel diagnostic approach for a type of malaria for which there is no reliable detection method.

The next day, I got a phone call saying that I couldn’t hold the grant because I was at a UK institute. It was pretty galling. The EU programme officer was helpful and sympathetic, but basically rules are rules.

How Brexit is changing the lives of eight researchers

I had to give up the principal-investigator position to a colleague at the Pasteur Institute in Paris and apply for €1.5 million of UKRI guarantee funding. The UKRI had to set up a system to deal with these orphaned grants, and for a good four to five months, we really didn’t know what was going to happen.

The work I did and the time I spent sorting this out was incredible. We started the project last October, but it’s still an administrative pain. We have visitors coming from Ethiopia, Madagascar and other partner countries, and we can’t support them because UKRI funding doesn’t support non-UK people. It’s unnecessarily complicated.

During the two years that the United Kingdom couldn’t be part of Horizon Europe schemes, people started not to think of the United Kingdom as a partner. We’re slightly excluded and it will take some time to recover. I just hope that it’s not too long. I’m proud that we’re going to get to do what we want to do, but I could have done without the hassle.

Michele Coti-Zelati had to turn down an ERC grant and apply for alternative funding.Credit: Tomas Bodnar

Michele Coti Zelati, mathematician at Imperial College London

I was awarded a €1.5-million ERC grant in March 2021 to build mathematical tools to study the stability and turbulence of fluids.

I was soon notified that in a few months, I would have to move to a Horizon Europe-affiliated country, or give up the grant. It’s hard for universities to give out permanent positions in three months. I would have had to go back to being a postdoc and hit the job market again in five years. It was a tough decision.

I heard that the grant would be covered by UK funders, but there was no official communication about this. So for a month, I was in limbo. I did then receive the same amount of funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. But I cannot take it outside the United Kingdom if I want to move.

I’m very happy that the United Kingdom is rejoining Horizon Europe. I wish that the deal came two years ago, when I was making this decision. I tried to delay the start of the project as much as possible to gain time, hoping for UK re-association with Horizon. If there was a possibility of keeping the ERC grant without moving, I would have done so. It’s a prestigious award.

Theresa Thurston hopes that the UK association with Horizon Europe will provide support for high-quality research.Credit: Teresa Thurston

Teresa Thurston, cellular microbiologist at Imperial College London

When I was awarded a €1.5-million ERC grant for a five-year project, the original assumption was that the United Kingdom would re-associate with Horizon Europe in time for me to accept it. At the beginning, I didn’t worry too much about the UK–EU situation and started doing the paperwork. But it quickly became evident that I would have to either move to an EU institution or decline the grant. That panicked me and a lot of others. We had a message board on Slack to share up-to-date information.

UK scientists are right to say no to ‘Plan B’ for post-Brexit research

In the end, I declined the grant and took the UKRI funding. It was too short notice to move to another country. Being a mother of three young children on top of everything, I wasn’t ready to mobilize and start doing interviews in the EU that quickly. It would have been very difficult to uproot my whole family.

I’ve now been able to start the work I wanted to with a delay. I’m grateful to have the UKRI money. But there is a loss of prestige from not having the connection to Europe — science is always stronger with collaboration.