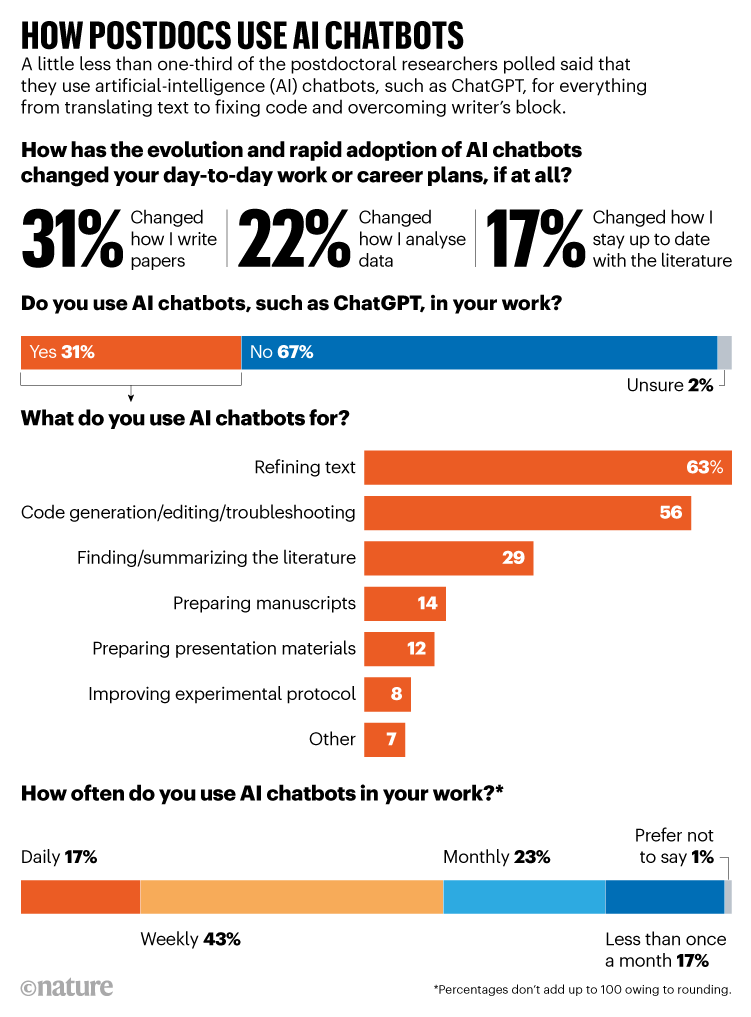

Around one in three respondents to Nature’s global postdoc survey are using AI chatbots to help to refine text, generate or edit code, wrangle the literature in their field and more.

Illustration by Fabrizio Lenci

After living in Japan for more than a decade, Rafael Bretas, originally from Brazil, speaks Japanese pretty well. Aspects of written Japanese, such as its strict hierarchies of politeness, still elude the postdoc. He used to write to senior colleagues and associates in English, which often led to misunderstandings.

Artificial-intelligence (AI) chatbots have changed all that. When the AI firm OpenAI, based in San Francisco, California, launched ChatGPT in November 2022, Bretas, who studies cognitive development in primates at RIKEN, a national research institute in Kobe, Japan, was quick to check whether it could make his written Japanese suitably formal. His hopes weren’t high. He’d heard that the chatbot wasn’t very good in languages other than English. Certainly, experiments in his own language, Portuguese, had resulted in text that “sounded very childish”.

But when he sent some chatbot-tweaked letters to Japanese friends for a politeness check, they said that the writing was good. So good, in fact, that Bretas now uses chatbots daily to write formal Japanese. It saves him time, and frustration, because he can now get his point across immediately. “It makes me feel more confident in what I’m doing,” he says.

Since ChatGPT’s launch, much has been written about its ability to disrupt professions, including fears of job losses and damaged economies. Researchers immediately began experimenting with the tool, which can assist in many of their daily tasks, from writing abstracts to generating and editing computer code. Some say that it’s a great time-saving device, whereas others warn that it might produce low-quality papers.

Last month, Nature polled researchers about their views on the rise of AI in science, and found both excitement and trepidation. Still, few studies have been published on how researchers are using AI. To get a better handle on that, Nature included questions about the use of AI in its second global survey of postdocs, in June and July. It found that 31% of employed respondents reported using chatbots. But 67% did not feel that AI had changed their day-to-day work or career plans. Of those who use chatbots, 43% do so on a weekly basis, and only 17% use it daily, like Bretas (see ‘How postdocs use AI chatbots’).

Those proportions are likely to change rapidly, says Mushtaq Bilal, a postdoc studying comparative literature at the University of Southern Denmark in Odense, who frequently comments on academic uses of AI chatbots. “I think this is still quite early for postdocs to feel if AI has changed their day-to-day work,” he says. In his experience, researchers and academics are often slow to adopt new technologies owing to institutional inertia.

It’s difficult to say whether the level of chatbot use found in Nature’s postdoc survey is higher or lower than the average for other professions. A survey carried out in July by the think tank Pew Research Center, based in Washington DC, found that 24% of people in the United States who said that they had heard of ChatGPT had used it, but that proportion rose to just under one-third for those with a university education. Another survey of Swedish university students in April and May found that 35% of 5,894 respondents used ChatGPT regularly. In Japan, 32% of university students surveyed in May and June said that they used ChatGPT.

The most common use of chatbots reported in the Nature survey was to refine text (63%). The fields with the highest reported chatbot use were engineering (44%) and the social sciences (41%). Postdocs in the biomedical and clinical sciences were less likely to use AI chatbots for work (29%).

Xinzhi Teng, a radiography postdoc at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, says that he uses chatbots daily to refine text, prepare manuscripts and write presentation materials in English, which is not his first language. He might, he says, ask ChatGPT to “polish” a paragraph and make it sound “native and professional”, or to generate title suggestions from his abstracts. He goes over the chatbot’s suggestions, checking them for sense and style, and selecting the ones that best convey the message he wants. He says that the tool saves him money that he would previously have spent on professional editing services.