Thermo Fisher Scientific and Lacks’s family reach a deal over the unethical use of her cells.

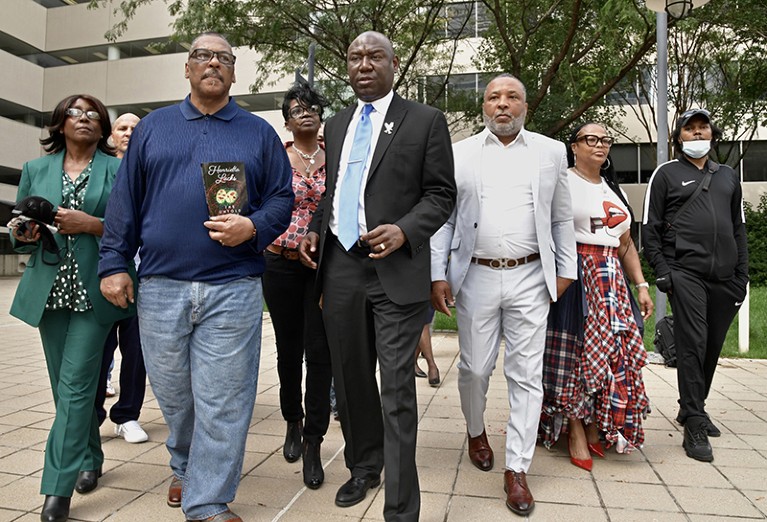

Members of Henrietta Lacks’s family walk with attorney Ben Crump (centre) ahead of announcing their lawsuit against Thermo Fisher Scientific in 2021.Credit: Amy Davis/Baltimore Sun/Tribune News/Getty

Earlier this week, the biotechnology company Thermo Fisher Scientific reached a settlement with the family of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who had cells taken from her and used for research without consent more than 70 years ago. The cervical cancer cells, removed during Lacks’s treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, and known as HeLa cells, were shared widely because of their ability to survive and divide indefinitely in the laboratory — and have led to numerous scientific discoveries. Eventually, they made their way into the hands of companies such as Thermo Fisher in Waltham, Massachusetts, which sells products derived from the cells.

Wealthy funder pays reparations for use of HeLa cells

The settlement, which remains confidential, comes after years of grappling by research institutions and biologists over how to use the cells ethically while also giving the Lacks family agency over them.

Nature spoke to legal specialists and researchers about what this settlement might mean for the scientific community, as well as for future litigation of this type.

“It does open up a conversation about needing to know, where do things come from initially, and what if terrible and awful, horrific things happen?” says Caprice Roberts, a legal specialist at Louisiana State University Law in Baton Rouge, who submitted an amicus brief supporting the lawsuit that the Lacks family filed in 2021 against Thermo Fisher. “This case law is the precedent for that, and it’s very historic for that reason — groundbreaking.”

According to a press release by the Lacks family’s lawyers, both parties “are pleased that they were able to find a way to resolve this matter outside of Court” and have no further comment about the settlement.

The grim story behind Lacks’s cells entered the mainstream after journalist Rebecca Skloot published a book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, in 2010. The book “shined a very bright light” on the non-consensual use of Henrietta’s cells — which by that point had become “ubiquitous” in research — says Carrie Wolinetz, a science-policy specialist at Lewis–Burke Associates, a government-relations firm in Washington DC with a focus on higher-education advocacy.

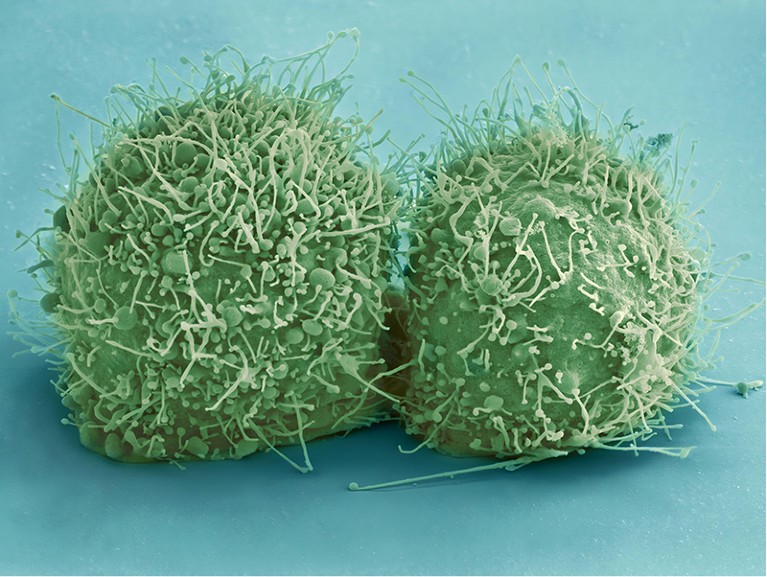

The beauty of HeLa cells “is that they grow in almost any type of media”, says Ivan Martinez, a cancer biologist at West Virginia University in Morgantown. “You can do many different types of studies with them, from basic biology experiments to understand, for instance, how chromosomes divide, to [application-based studies] like testing drugs or developing vaccines.” The cells have been instrumental in at least three Nobel-prizewinning discoveries, but Lacks’s family was not compensated for those uses.

HeLa cells, as shown in this scanning-electron-microscope image, have been crucial to the development of vaccines and other prize-winning discoveries.Credit: BSIP SA/Alamy

After Skloot’s book was published, many institutions began wrestling with their part in the cells’ exploitation. For instance, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research, opened a dialogue with the Lacks family that culminated in the decision to create a HeLa cell working group. The group reviews research proposals and decides whether to give access to projects requiring the full DNA sequence, or genome, of the cells.

The creation of this group was intended to show “that transparency in and of itself was really important in terms of demonstrating respect for Henrietta Lacks’s contributions and those of her family”, says Wolinetz, formerly a senior adviser at the NIH Office of the Director.

In the wake of protests over racial justice in 2020, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) in Chevy Chase, Maryland, announced a six-figure gift to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation, which was founded by Skloot and aims to provide assistance to individuals and family members who have been affected by non-consensual medical studies.

That action was triggered by a decision taken by the lab of Samara Reck-Peterson, a cell biologist at the University of California, San Diego, in La Jolla, to make its own donation. As the lab debated its use of the cells, “it occurred to us that we should actually talk to the family”, says Reck-Peterson, an HHMI investigator. “They are extremely proud of the science that had been done because of their grandmother and great-grandmother’s cells, so they absolutely didn’t want us to stop doing research with the cells.” The lab decided to make donations for any cell line it had already created from HeLa cells and any line it created in future.

The Thermo Fisher settlement is the first of its kind.

Christopher Ayers, one of the lawyers representing the Lacks family, suggests that other lawsuits might follow. “There are other companies that know full well the deeply unethical and unlawful origins of the HeLa cells and choose to profit off of that injustice,” he says. “To those that are not willing to come to the table and do right by the family, we will pursue litigation.”

Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong

But Ayers notes that the circumstances under which Lacks’s cells were taken from her are unique, and that this case’s outcome might not extrapolate to others involving the use of ‘medical waste’ in research. “Litigation on behalf of the Lacks family would not open the floodgates to litigation by others that have voluntarily donated tissue or cells for other types of medical research,” he says.

Other specialists say that the case does play into a larger discussion regarding the use of people’s tissue or other biological specimens in research. Much of the human tissue used in medical research is ‘waste’ discarded during surgery. Even if a person consents to a procedure, they should “have the legal right to decide whether to allow the use or not of cells derived” from it, says Stephen Sodeke, a bioethicist at Tuskegee University in Alabama.

Wolinetz says that even today there could be a scenario in which a cell line or other sample is taken from a person and is ‘anonymized’ so that it isn’t associated with that individual, then leads to massive medical discoveries without the person knowing. To avoid this situation, she says, it would be worthwhile setting up systems that allow patients to consent to a broader use of their cells, although this would be a logistical challenge. And, she adds, researchers would want to avoid setting up any monetary incentives that would coerce people into donating samples they otherwise wouldn’t.

As for what the Thermo Fisher settlement means for other companies profiting from biological specimens, it puts the onus on them to do due diligence on how ethically their samples were sourced — even if they didn’t collect them, Roberts says.