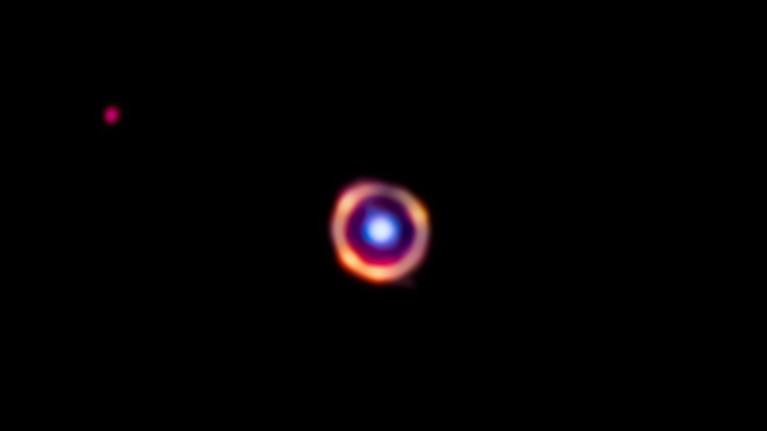

A galaxy (blue; artificially coloured) helped to give the JWST a better view of organic molecules (bright orange spots) in a second galaxy.Credit: J. Spilker/S. Doyle, NASA, ESA, CSA

Tangles of huge organic molecules are drifting through a faraway galaxy, astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered. Scientists have never spotted such molecules so far from Earth, and their presence suggests that their host galaxy was busy creating stars early in the history of the Universe.

The galaxy lies 3.8 billion parsecs (12.3 billion light years) away — so distant that it appears as it did less than 1.5 billion years after the big bang. “It must have basically formed on overdrive,” says Justin Spilker, an astronomer at Texas A&M University in College Station.

Spilker and his colleagues describe the finding today in Nature1. It shows the power of the new JWST, even as the spectrometer aboard the telescope that made the measurement has experienced a sudden and surprising degradation in performance.

Photobombing galaxy

As seen from Earth, the galaxy, known as SPT0418-47, happens to lie behind another, closer galaxy. The gravity of the intervening galaxy bends and distorts the light from SPT0418-47, making it some 30 times brighter than it would otherwise appear — an effect called gravitational lensing.

JWST spots planetary building blocks in a surprising galaxy

Spilker’s team wanted to find polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are chemical compounds that are found in soot and smoke. They also form near young, massive stars that emit a lot of ultraviolet light.

Feeding off that energy, the molecules grow large and eventually resemble smoke or soot particles floating in space. They help to regulate how gas within galaxies is heated and cooled, and thus help to control how new stars are born, says Stacey Alberts, an astronomer at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Earlier studies of SPT0418-47 had spotted areas where stars might have been forming, but could not detect PAHs2. The molecules are hard to spot except in infrared wavelengths of light, which JWST excels at studying. So Spilker’s team pointed the telescope at the galaxy last August, in what were some of its first science observations. Months later, they finally had the data processed, and the PAHs emerged.

The molecules appear as bright patches inside the galaxy’s ring. That patchiness surprised Spilker. “Everywhere we see the molecules there are stars forming — but there are also parts in that ring where there are stars forming where we don’t see the molecules,” he says. “That’s the part we don’t really understand yet.”

Regardless, the PAHs suggest that the galaxy was busy making stars early in the Universe’s history. At a time when the Universe was just 10 percent of its current age, SPT0418-47 already had a mass similar to that of today’s Milky Way.

Other JWST observations have spotted PAHs in nearby galaxies3. But seeing PAHs in this distant galaxy is an important clue to how these molecules form, says Karin Sandstrom, an astronomer at the University of California San Diego. They are “quite mysterious still, and we don’t fully understand how they form even in the Milky Way”, she says. Alberts adds that the new discovery will force astronomers to “rethink how dust first formed and how that shaped the early generations of stars and galaxies”.

JWST reveals first evidence of an exoplanet’s surprising chemistry

More discoveries might be on the way — or not. Spilker and his colleagues are planning to use JWST to hunt for PAHs in two other gravitationally lensed galaxies. But the telescope’s mid-infrared spectrometer, which is what the team used to study SPT0418-47, is currently experiencing problems.

On 25 May, the team that operates JWST reported that the spectrometer was not gathering as much information as it is supposed to in one of the modes in which it operates. Two of the four channels in which it observes in that mode are degrading, in the worst case losing up to 50% of the data.