Oceanographer Peter Girguis offers an insider view of deep-sea exploration.

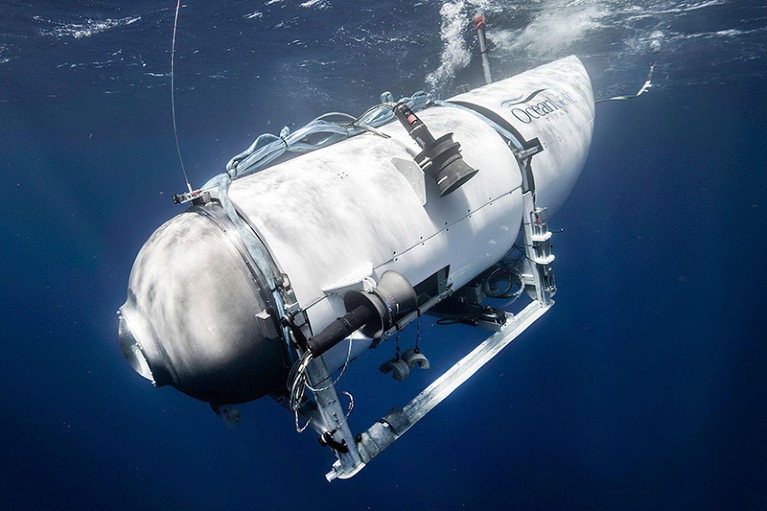

The 5-person crew aboard OceanGate’s submersible Titan lost contact with their mothership about 1 hour and 45 minutes after beginning their dive.Credit: American Photo Archive/Alamy

Update: On 22 June, pieces of the Titan submersible were found on the sea floor nearly 500 metres from the bow of the Titanic. Search officials said that the sub experienced a catastrophic implosion, and concluded that all five passengers are dead.

As the world watches the international effort to locate the submersible vessel Titan — which lost communication with its mothership on 18 June off the Canadian coast while taking five passengers to visit the wreckage of the Titanic — rescuers are scrambling to understand what went wrong.

Diving deep: the centuries-long quest to explore the deepest ocean

Media outlets have reported that the company operating the Titan, OceanGate, had received warnings before about the safety of its craft, meant to carry wealthy clientele on excursions. Specifically, a 2018 lawsuit against the company warned that the Titan had not been designed to withstand pressures at the extreme depths — nearly 4,000 metres below the ocean’s surface — where the Titanic is located. Other concerns about circumventing conventional prototype testing were also raised.

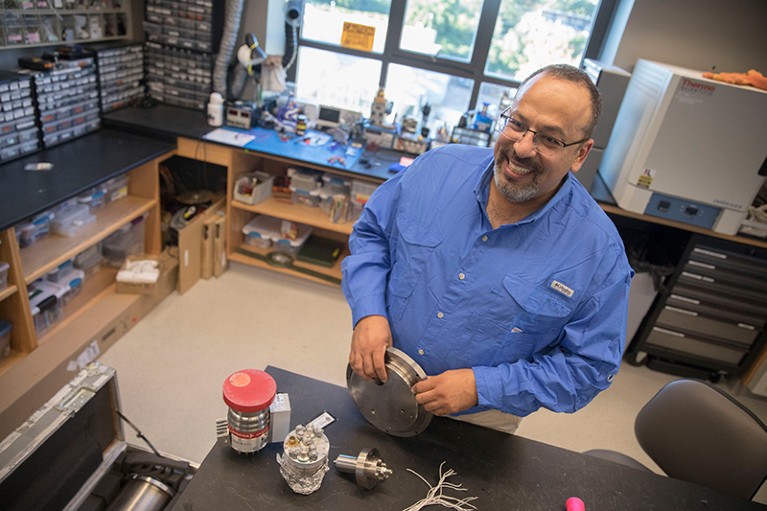

Nature spoke to Peter Girguis, an oceanographer at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to see whether his own research expeditions exploring the deep ocean can offer any insights into the Titan’s capabilities, possible rescue efforts as the vessel runs out of oxygen and what this unfolding disaster might mean for future science missions.

Throughout my career, I’ve used crewed submersibles to do research [on the geological processes that affect marine organisms] in the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. Research submersibles are purposely designed to simply and safely move scientists to and from the sea floor, and they have been around for the better part of half a century.

Most research submersibles hold two or three occupants, and are lowered into the water by a mothership. The submersible is then untethered and descends to the sea floor on its own. We remain inside the vehicle and use robotic manipulators [to collect samples].

There are also a lot of remotely operated vehicles that are controlled from the ship. They are essentially robots on the end of a leash. We work with them in the deep ocean because they are less of a risk in many ways. They’re also able to stay down for hours and days without having to return to the surface.

Oftentimes, if it’s a new place, we will send a robot down to get the lay of the land, and then we will take a crewed submersible down, because it’s hard to beat that in-person experience.

Oceanographer Peter Girguis of Harvard University.Credit: Kris Snibbe/Harvard University

The Titan is a unique submersible. It is made out of a composite hull, and is shaped a bit more like a scuba tank, whereas the research submersibles that we scientists use are spheres. Titan really was not designed with research in mind: it was designed to carry five people, instead of two or three, to the sea floor. The Titan, to my knowledge, does not have manipulators for sampling. It does not have any of the scientific equipment we might use for measurements, and it does not appear to have some of the other kinds of sensors, beacons and other systems that we use in research, that are also important just to maintain contact.

Exactly. There is a particular kind of beacon that is used to help the submersible navigate on the sea floor. There is no GPS under water. There’s no Wi-Fi. There’s no Bluetooth. When we are under water, the way we know our position is through this beacon, and it’s in constant contact with the ship. That’s critical for the science: if we want to know where we made an observation or collected a sample, we really do have to have a latitude, longitude and depth and all the geochemical measurements. It is also useful in helping the ship keep track of the submersible.

The beacons to which I’m referring are commercially available. They are used both by industry vehicles, as well as academic vehicles, and they have been a major advance in our ability to geolocate objects on the sea floor.

From what I know about how the Titan is configured, I do not see manipulators on the vehicle, so they’re certainly not going to be sampling. It is reasonable to think that the Titan could be doing video observations of the Titanic. For an archaeologist, that is really potent data. It is not, though, the same as a research submersible by any stretch.

Sending a crewed submersible down is the worst idea. Crewed submersibles have a limited time under water for safety reasons. Crewed submersibles are also potentially at risk of being entangled [in Titanic wreckage] in the same way that the Titan might be. There are plenty of remotely operated robotic submersibles that work at a depth of 6,500 metres, and would be an ideal asset to get on site to assist the Titan. The real challenge, of course, is how do you get out to this remote location in the Atlantic in time?

I really have no idea how operators and government agencies will respond to this incident with respect to research submersibles. We still do not know where the Titan is. Or the status of the crew. As we continue to learn more about what went sideways with the Titan, I expect we’ll pause and give some thought as to how it applies to research submersibles.

OceanGate, as I understand it, really sought to push the technology and, in a way, make trips to the sea floor as turnkey as possible. I’m concerned that they overlooked some of the features that we build into research submersibles, because they struck [the builders] as costly or unnecessary, or uninteresting. A lot of those features that we see across submersibles have evolved over decades, precisely because they work, and because we know it increases safety for the crew.