Just 100 years ago, we understood astoundingly little about sleep and dreaming. A tight-knit band of researchers changed things, against sometimes considerable odds.

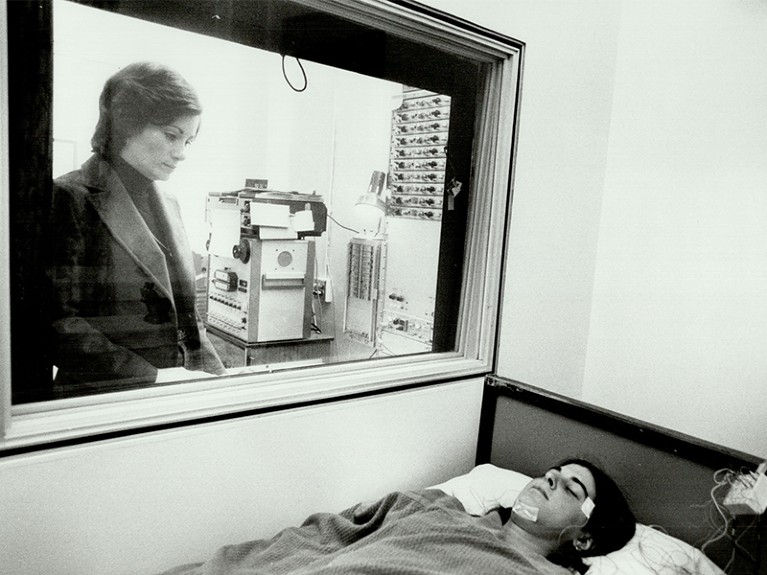

Sleep became a scientific discipline only in the twentieth century.Credit: Tony Bock/Toronto Star/Getty

Mapping the Darkness: The Visionary Scientists Who Unlocked the Mysteries of Sleep Kenneth Miller Hachette (2023)

Sleep and dreaming are human universals. Yet only in the past century has science begun to appreciate how centrally important they are for many facets of our health and well-being, and to address the many, profound questions that sleep and dreaming pose. Why do humans sleep, and what happens when they don’t? What is happening when someone dreams? What constitutes ‘good’ sleep — and how can physicians diagnose and treat disordered sleep?

It is rare that the history of a scientific field and the emergence of a medical sub-speciality are eloquently summarized in a single volume. In Mapping the Darkness, journalist Kenneth Miller achieves just that, with the tale of how pioneering researchers created the scientific and clinical discipline of sleep. In reading it, one is struck by just how much scientists didn’t know 100 years ago. Many great discoveries are accidents of history meeting genius and determination, and Miller’s story exemplifies how the personal qualities of individuals can shape an entire field — to the benefit of us all.

Deep asleep? You can still follow simple commands, study finds

In Miller’s account, the sleep-science journey begins with the birth of Nathaniel Kleitman in Russia in 1895. Kleitman was a brilliant, driven man whose early life was marked by hardship: his father met an untimely death, leaving his mother to raise him alone, and his childhood was plagued by antisemitism. The exclusion of Jewish students from Russian universities led him to seek advanced studies elsewhere, eventually in the United States. He enrolled in the PhD programme at the University of Chicago, Illinois, where he would begin and end his career as a sleep researcher.

The book gives an honest account of Kleitman as a teacher and mentor. He was neither charismatic nor overtly friendly. But he was determined to find answers to seemingly unanswerable questions, against sometimes considerable odds, and to share his findings. Perhaps the most immediately intriguing question was: why do humans, with our highly evolved brains, need to settle in for 8 hours of slumber every night at the expense of other, more obviously productive activities? Similarly, why is it that our physical and mental functions deteriorate with lack of sleep?

The discovery that is often described as really beginning to answer these questions, kick-starting the field of sleep research, occurred in the early 1950s. It was then that Kleitman’s graduate student Eugene Aserinsky noticed a pattern of brain activity and eye movements during sleep that would ultimately be called REM sleep — the stage in which most dreams occur. Around the same time, William Dement joined Kleitman’s laboratory as Aserinsky’s assistant. Intrigued by the teachings of Sigmund Freud, which had led him to study psychiatry, Dement quickly learnt the lab’s methods and contributed to its findings on REM sleep and dreaming. He went on to medical school and developed the first clinical programme focused on sleep disorders, based at Stanford University in California.

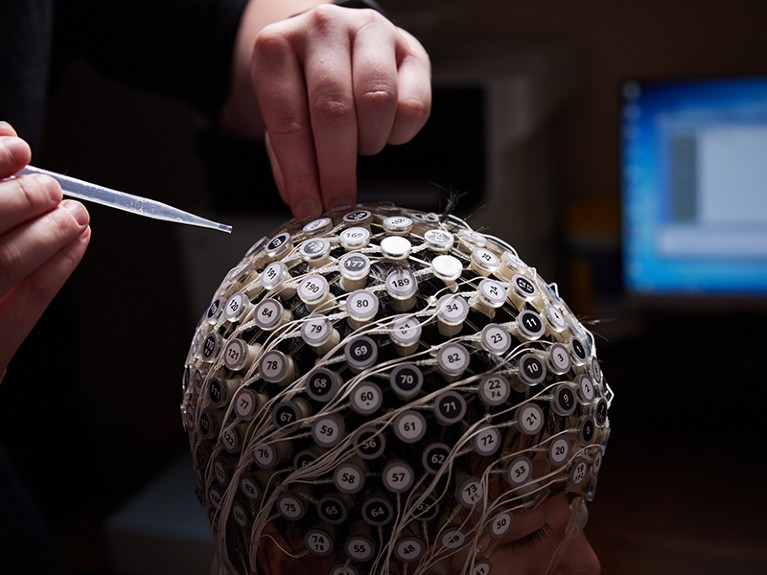

Sleep-science pioneers did without modern tools such as electroencephalograms (pictured).Credit: Leah Nash for the Washington Post/Getty

Like most people in the field, I met Dement on many occasions, and have my own stories about his warmth and positivity. The book shares not only his successes, but also his struggles — he had a difficult childhood, like Kleitman, and experienced personal tragedies in his adult life. The challenges the early sleep scientists faced without modern technology such as electroencephalograms to measure electrical activity in the brain, or the computing power to analyse the signals, were enormous. Furthermore, sleep science was not well-regarded in its early days, and Dement struggled, as Kleitman had, to maintain funding for his research and clinical work. Yet he persevered, and is credited with permanently establishing sleep research as a discipline worthy of dedicated resources.

Another central character is Mary Carskadon, a relative of Dement’s by marriage and an astonishingly accomplished researcher in her own right. She pioneered the study of sleep in children and developed a standardized measure of sleepiness, known as the multiple sleep latency test. It is now considered the ‘gold standard’ measure of sleepiness during the day, and is used in the diagnosis of disorders involving excessive drowsiness. Now at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, Carskadon is humble, hardworking and dedicated to her craft. I had the exceptional good fortune of spending a year in her lab while doing my clinical psychology internship at Brown more than 20 years ago. I am not alone. The academic family tree of Kleitman, Dement and Carskadon has branches that reach around the world.

The final section of the book turns to the emergence of sleep as a discipline in medicine. In the late 1970s, Colin Sullivan, then a physician and researcher at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, Australia, noted that obstructive sleep apnoea, a condition in which normal breathing is disrupted during sleep, was not simply an uncommon occurrence in men with obesity as had been thought, but a much more prevalent sleep disorder. At the time, the only available treatment was tracheotomy — making a cut in the windpipe. Sullivan’s invention, in the 1980s, of positive airway pressure therapy (essentially blowing air down the sleeper’s throat to keep it open) was inspired by endoscopic videos of airway collapse shared by Christian Guilleminault, a French researcher who spent his career at Stanford University alongside Dement. It revolutionized care for people with this condition.

Sleep loss impairs memory of smells, worm research shows

Progress was seen around the same time on the diagnosis and treatment of narcolepsy — in which individuals experience severe sleepiness and related symptoms — and insomnia. For many years, only addictive drugs such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines were available to treat insomnia. The work of many scientists allowed a different conceptualization of the condition, opening the way to behaviourally based treatment such as stimulus-control therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy.

The study of circadian rhythms has emerged alongside sleep research and sleep medicine in recent decades, and the paths between these disciplines weave together like vines. A separate volume would probably be needed to recount that tale fully. This book engagingly tells the story of a young scientific and medical discipline that is still spreading its wings. As a sleep scientist and specialist in behavioural sleep medicine myself, I feel fortunate that foundational discoveries are still being made in our field, and that many of its founders are still with us as teachers, mentors and friends. Although this book is about sleep science, it also pays tribute to the pioneers who were first unafraid to ask what lies in the darkness.