The majority of sequences come from people who lived in Western Eurasia, but samples from other regions are on the rise.

These 2000-year-old human remains were found in a stone chambered cairn in Greenland. Advances in DNA sequencing have prompted to a rapid increase in ancient-genome research.Credit: Ashley Cooper/Getty

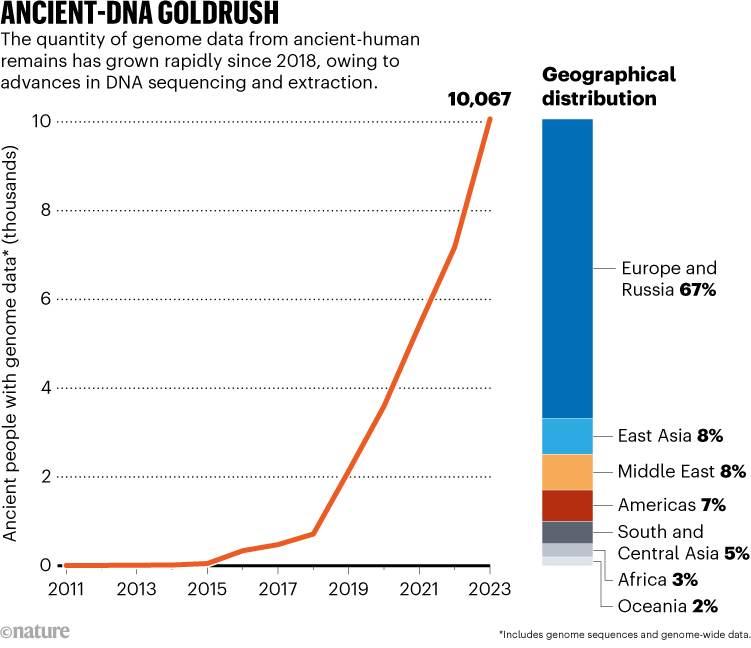

In 2010, researchers published the first genome sequence from an ancient human, using tufts of hair from a man who lived around 4,000 years ago in Greenland1. In the 13 years since, scientists have generated genome data from more than 10,000 ancient people — and there’s no sign of a slowdown.

“I feel truly gobsmacked that we have gotten to this point,” says David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts. His team maintains a database of published ancient-human genome data, called the Allen Ancient DNA Resource, which was described this month in a preprint study on bioRxiv2.

Sources: Ref. 2, D. Reich

Before 2010, ancient-DNA studies focused on limited stretches of DNA, such as the roughly 16,500-base-pair-long mitochondrial genome or short segments of the nearly 3.1 billion base pairs in the human genome. Since then, advances in DNA sequencing have made it feasible to decode entire ancient genomes. Initially, this process was labour-intensive, and relied on finding rare samples with high levels of genuine ancient DNA. As a result, it took several years to generate genome data from a dozen individuals.

Each year since 2018, researchers have produced genome data from thousands of ancient humans, thanks to technological advances in DNA sequencing and extraction methods. For many samples — including those from Reich’s lab — researchers sequence a set of one-million DNA bases that tend to vary between people, instead of an entire genome, which is much costlier.

The field’s exponential growth has also been propelled by a focus on more recent samples from the 12,000 years since the last ice age ended, which are more abundant and tend to have higher-quality DNA than older human remains.

The vast majority of ancient-human genomes come from people who lived in Western Eurasia, an area encompassing Europe, Russia and the Middle East. Since 2012, most genomes have come from Europe and Russia, although there has been a modest decline in that proportion since 2015.

Sampling from other regions, particularly East Asia, Oceania and Africa, is becoming more frequent. Africa’s centrality to the human story means that it is especially important for its proportion to grow, says Reich, who was part of a team that published the largest-yet ancient-genome study from Africa last month3.

Divided by DNA: The uneasy relationship between archaeology and ancient genomics

Ancient-human genomes might be growing in number and global diversity, but this is being driven by a small number of labs, says María Ávila-Arcos, a palaeogenomicist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City. “They hop region to region to address these big questions and sequence as many genomes as they can.”

As ancient genomics becomes increasingly global, Ávila-Arcos would like researchers to generate smaller numbers of genomes — sparing precious samples — to address questions important to communities and scientists in the regions where they originate. “We need to shift that focus and obsession with numbers,” she says.

Nearly 80% of ancient-human genome sequences in the database come from just three institutions, according to Reich, whose own group contributed nearly half of the total (others are based at the University of Copenhagen and two Max Planck Institutes). Building the capacity to do ancient genomics in under-represented parts of the world is “extremely important”, says Reich, who is attending a conference in Kenya next month called DNAirobi, with this goal in mind.