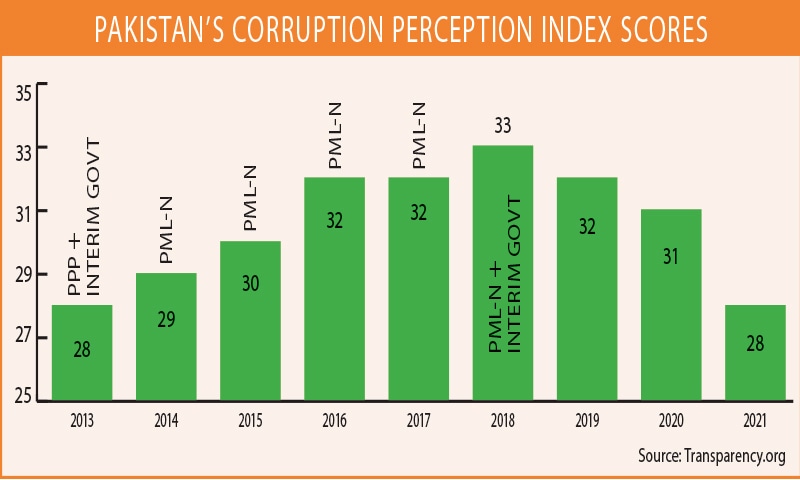

Having said that, it is important to recognize that a sustained decline in corruption perceptions is bad for a country, especially one seeking foreign direct investment. As someone who has worked with foreign investors seeking to deploy capital abroad, I am quite familiar with the way a country is ranked among a peer group before a decision is made to conduct a deep dive into the political economies of a shortlist.

The initial task of conducting this exercise falls to a small team of analysts, mostly below 30 years of age. These analysts collect data such as the World Bank Ease of Doing Business rankings (before it was scrapped by the World Bank), the World Economic Forum’s Competitiveness Index, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Country Risk Ratings, and Transparency International’s CPI. All this data is tabulated in an Excel file and relative weights are given to each measure based on the type of investment being considered.

For example, a major infrastructure project with high government involvement and debt financing will command higher weightage to country risk ratings and corruption perceptions, while a funding round for a technology startup will focus more on indices measuring digital connectivity and internet access.

Based on this tabulation, a shortlist of countries is prepared for deeper assessment to determine political risk, financial risk, execution risk, etc. As this process is conducted, investment teams project the risk premium in a financial model and develop high-level budgets for things like compliance monitoring, legal support, etc. These budgets are determined based on initial conversations with in-country experts as well as a country’s trajectory in rankings and scores across a whole host of indices, including the CPI.

What this means is that a country like Pakistan, which is experiencing a declining score in the CPI and witnessing economic and political instability (as evidenced by rising inflation, debt, and extremist violence), will find it difficult to make it to the shortlist. And even if it does, the risk premium in the financial models being developed to seek the investment committee’s approval will be high. This would then make the overall project costlier compared to other countries with a lower risk profile, meaning that the investment committee would likely decide against choosing Pakistan.

It is for this reason that improving rankings in indices such as the CPI is vital. Without doing so, the risk premium on a country like Pakistan will remain above the tolerance levels of a significant portion of international investors looking at Pakistan and other peer economies.

Another reason why the declining score in the CPI ought to concern Pakistanis is because the ruling party’s rhetoric about corruption has not translated into an improvement in perceptions among a narrow segment of society. As detailed CPI data shows, Pakistan’s score has declined significantly in four of the eight measures that make up the CPI:

Finally, there is the baggage of the ruling PTI’s own rhetoric, where senior leaders including Prime Minister Imran Khan used to chide the opposition about corruption using CPI data. Now that they are in power, the party’s leaders and social media teams are spinning a different narrative.

Despite the political rhetoric on either side of the aisle, it is important to remember that the CPI is at best a flawed indicator of corruption in any society. The index may have some value for some actors, but it does not tell the full story when it comes to corruption in a society. To credibly deal with the corruption challenge, it is important for successive governments to focus on improving the rule of law, promoting transparency, and reducing bureaucratic red tape.

These actions, as I argued in another article, must “be informed by research that highlights why corruption is pervasive, what its transmission mechanisms are, and the type of systemic reforms that may succeed in reducing the incentive for people to grease the system.”