Search giant is amassing health records from Ascension facilities in 21 states; patients not yet informed

Google launched the effort last year with Ascension, the country’s second-largest health system.

PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG NEWS

By Rob Copeland

Updated Nov. 11, 2019 4:27 pm ET

Google is engaged with one of the U.S.’s largest health-care systems on a project to collect and crunch the detailed personal-health information of millions of people across 21 states.

The initiative, code-named “Project Nightingale,” appears to be the biggest effort yet by a Silicon Valley giant to gain a toehold in the health-care industry through the handling of patients’ medical data. Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corp. are also aggressively pushing into health care, though they haven’t yet struck deals of this scope.

Google began Project Nightingale in secret last year with St. Louis-based Ascension, a Catholic chain of 2,600 hospitals, doctors’ offices and other facilities, with the data sharing accelerating since summer, according to internal documents.

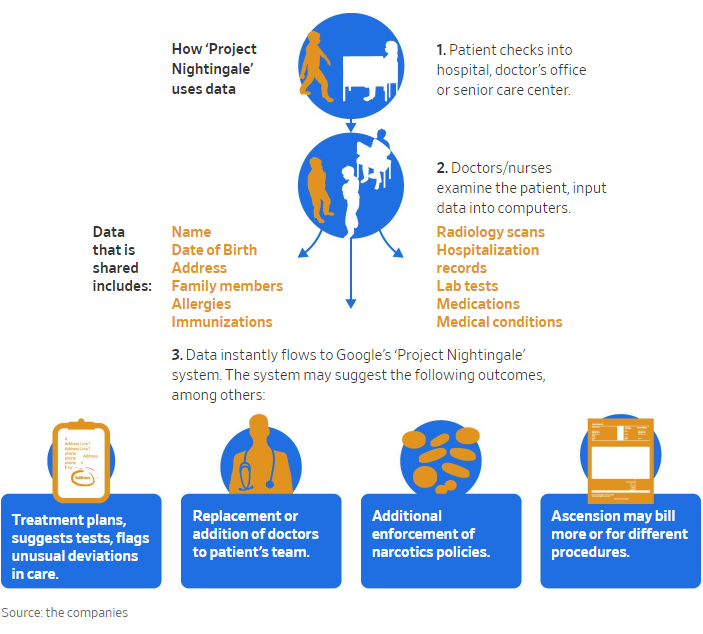

The data involved in the initiative encompasses lab results, doctor diagnoses and hospitalization records, among other categories, and amounts to a complete health history, including patient names and dates of birth.

The tech giant is teaming with Ascension on an ambitious project to crunch patient data for treatment and administrative purposes.

Neither patients nor doctors have been notified. At least 150 Google employees already have access to much of the data on tens of millions of patients, according to a person familiar with the matter and the documents.

In a news release issued after The Wall Street Journal reported on Project Nightingale on Monday, the companies said the initiative is compliant with federal health law and includes robust protections for patient data.

Some Ascension employees have raised questions about the way the data is being collected and shared, both from a technological and ethical perspective, according to the people familiar with the project. But privacy experts said it appeared to be permissible under federal law. That law, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, generally allows hospitals to share data with business partners without telling patients, as long as the information is used “only to help the covered entity carry out its health care functions.”

Google in this case is using the data in part to design new software, underpinned by advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning, that zeroes in on individual patients to suggest changes to their care. Staffers across Alphabet Inc., Google’s parent, have access to the patient information, internal documents show, including some employees of Google Brain, a research science division credited with some of the company’s biggest breakthroughs.

Google Cloud President Tariq Shaukat said the company’s goal for health care is centered on “ultimately improving outcomes, reducing costs, and saving lives.”

Eduardo Conrado, an executive vice president at Ascension, said: “As the health-care environment continues to rapidly evolve, we must transform to better meet the needs and expectations of those we serve as well as our own caregivers and health-care providers.”

Google and nonprofit Ascension have parallel financial motives. Google has assigned dozens of engineers to Project Nightingale so far without charging for the work because it hopes to use the framework to sell similar products to other health systems. Its end goal is to create an omnibus search tool to aggregate disparate patient data and host it all in one place, documents show.

The project is being developed under Google’s cloud division, which trails rivals like Amazon and Microsoft in market share. Google Chief Executive Sundar Pichai has said repeatedly this year that finding new areas of growth for cloud is a priority.

Ascension, the second-largest health system in the U.S., aims in part to improve patient care. It also hopes to mine data to identify additional tests that could be necessary or other ways in which the system could generate more revenue from patients, documents show.

Ascension is also eager to have a system that is faster than its existing decentralized electronic record-keeping.

Google, like many of its Silicon Valley peers, has at times drawn criticism for not doing enough to protect user privacy. Its YouTube unit agreed in September to pay $170 million in fines and change its practices in response to complaints that it illegally collected data on children to sell ads. YouTube neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing.

Last year, the Journal reported that Google opted not to disclose to users a flaw that exposed hundreds of thousands of birth dates, contact information and other personal data of subscribers in its now-defunct social-networking website Google Plus, in part because of fears that the incident could trigger regulatory scrutiny. Google said at the time it went beyond legal requirements in determining not to inform users.

Regulators are now scrutinizing the company on a number of fronts. Federal and state investigators over the summer made public separate antitrust inquiries into Google. The federal probe is examining whether Google’s existing trove of data amassed from its flagship search engine, home speakers, free email service and numerous other arms give the company an unfair advantage over competitors, people familiar with the matter said.

Google has said its products increase consumer choice and that it is committed to cooperating with the inquiries. This year, Mr. Pichai has touted new privacy protections for Google’s billions of users.

The company made public this month a $2.1 billion deal for wearable fitness maker Fitbit Inc., which makes watches and bracelets that track health information like a person’s heart rate. Politicians of both parties quickly criticized the deal; Rep. David Cicilline (D., R.I.), chairman of the House Antitrust Subcommittee, warned that the Fitbit deal would give Google “deep insights into Americans’ most sensitive information.”

The companies said they would be transparent about any Fitbit data they collect.

Google appears to be sharing information within Project Nightingale more broadly than in its other forays into health-care data. In September, Google announced a 10-year deal with the Mayo Clinic to store the hospital system’s genetic, medical and financial records. Mayo officials said at the time that any data used to develop new software would be stripped of any information that could identify individual patients before it is shared with the tech giant.

Google was founded with the goal of organizing the world’s information, and health has been a fascination of its top executives from the early days. Google Health, a fledgling effort to digitize existing medical records, was shut down in 2011 after three years of limited adoption. Alphabet has since poured millions of dollars into its under-the-radar Calico and Verily divisions, which aim to combat aging and manage disease, respectively.

Google co-founder Larry Page, in a 2014 interview, suggested that patients worried about the privacy of their medical records were too cautious. Mr. Page said: “We’re not really thinking about the tremendous good that can come from people sharing information with the right people in the right ways.”

Write to Rob Copeland at rob.copeland@wsj.com

Article written by Rob Copeland and posted on the WSJ.com.

Article reposted on Markethive by Jeffrey Sloe