Withdrawal from deduction

The power struggle in Sudan escalates. It would be irresponsible to withdraw the UN blue helmets from Darfur as planned.

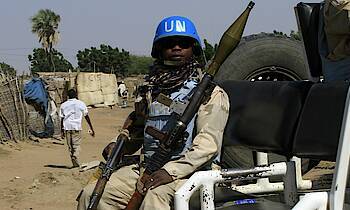

The mission in Darfur is one of the largest missions in UN history.

Sudan is currently the focus of world attention, initially because of the hope of a peaceful change of power after the fall of dictatorship al-Bashir, in recent weeks because of the bloody escalation of the power struggle between the military and the opposition. The situation is different in the case of Darfur. The conflict in the western Sudanese region has disappeared from the spotlight of international attention. And so last year, the decision of the UN Security Council to end the UN peacekeeping UNAMID fairly quickly was hardly noticeable. In view of unresolved conflicts and a fragile security situation, only a few observers questioned whether the right time for a withdrawal had actually come. But now this process is stalling because of the events in the capital Khartoum. A transfer of responsibility from UNAMID to the government of Sudan is hardly conceivable under the current circumstances.

In spring 2003, rebel groups rose up in Darfur against the Sudanese government, which they accuse of social, political and economic marginalization of the non-Arab population. According to UN estimates, the armed conflict between rebels and government troops and militias close to the government, the so-called Janjaweed, cost 300,000 lives. In 2007, the Security Council decided to deploy UNAMID (United Nations - African Union Hybrid Operation in Darfur), a UN peacekeeping force led by the UN and the African Union. With almost 20,000 blue helmets, it is one of the largest operations in UN history.

More than a decade later, in mid-2018, the Secretary General presented a detailed plan that would see UNAMID fully withdrawn by 2020. Sudan had been pushing for an end to UNAMID for some time. At the UN headquarters in New York, the gradual withdrawal was considered responsible due to positive trends. And the Security Council is trying anyway - even at the urging of the Americans - to provide the large, expensive and long-lasting missions with an exit strategy. So it was agreed.

The implementation progressed quickly; The majority of the emergency services have already been withdrawn and a number of locations have been closed. In large parts of Darfur, the UN is now pursuing a peacebuilding-oriented approach; the remaining peacekeeping capacities are mainly concentrated in the troubled region of Jebel Marra. Only 4 050 soldiers and 2 500 police officers are still active. Its priority tasks include protecting the civilian population, supporting humanitarian aid, mediating between the government and rebel groups and in local conflicts.

The security situation in Darfur has actually improved. However, this is not because the conflict has been resolved, but because of the government's successful military offensives.

Overall, the security situation in Darfur has actually improved. However, this is not because the fundamental conflict has been resolved, but primarily because of the government's militarily successful offensives against the majority of the rebels. Today only the Sudan Liberation Army-Abdul Wahid (SLA-AW) is still active in Darfur. The political process to resolve the conflict between the government and the rebels has been stagnating for years. "Darfur," the UN Secretary-General characterized the situation at the beginning of 2019, "has never been more stable since UNAMID was deployed, but the fundamental causes of the armed conflict in Darfur have not been fully resolved."

The conditions for the planned withdrawal of UNAMID are difficult anyway, even if it is based on a broad consensus and is technically well prepared. In no way can one speak of “mission accomplished”. In contrast to UN missions in West Africa, which were successfully completed in 2017 and 2018, the mission here should not be carried out because it would have fully implemented its mandate or the conflict would have been resolved. It is rather the case that there are hardly any opportunities to achieve more than before by staying longer. In short: UNAMID goes, the conflict remains.

It is also known that despite positive trends, the security situation remains fluid: the UN itself refers to fighting between government troops and SLA-AW in Jebel Marra, continuing violence against civilians and violent local conflicts. It was only in early June that UNAMID reported 17 deaths, further injuries and hundreds of burned-down houses after local clashes in Deleji in central Darfur.

Meanwhile, the situation in Sudan has also changed dramatically: since the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir in April 2019 and the takeover of power by a Transitional Military Council (TMC), the country has been in transition. The initial hope that the TMC and the civil protest movement will quickly agree on a kind of negotiated transition has now become illusory.

Immediately after the military came to power, the question arose for UNAMID and the UN Security Council whether it would be reasonable to continue the withdrawal if it is unclear who is providing the government.

Immediately after the military came to power, the question arose for UNAMID and the UN Security Council as to whether it would be justifiable to continue UNAMID's withdrawal, as long as it is unclear who the government is, how the relationship between civilians and the military is, or whether and where when elections take place. After all, the process is about handing over not only infrastructure but also security responsibility to the government of Sudan.

At the end of May, a UN report said that the overthrow in the capital had only a moderate impact on the security situation in Darfur. The negative effects of the previous UNAMID withdrawal on security are also limited. At the time, there was no reason to change the date for the end of the mission, but a reason for a gradual withdrawal. At the same time, it was criticized that part of the accommodation and facilities previously handed over by UNAMID to the government - contrary to all agreements - was being used by Sudanese security forces. In May, the UN headquarters in El Geneina was raided and looted the evening before the planned handover. Police and military uniforms are also believed to have been involved.

On June 3, the ongoing civilian protests in Khartoum were violently suppressed. Over 100 civilians are reported to have been killed, hundreds injured, and dozens raped. The violence is attributed to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). This militia emerged directly from the Janjaweed, who are held responsible for the murder and ethnic displacement in Darfur. The head of the RSF, General Hamdan Daglo, called Hemeti, is himself a former Janjaweed leader. Today he is formally number two in the military council, but apparently at least currently the strongest figure in the council. In any case, his militia has controlled the capital Khartoum since June 3.

Germany and Great Britain, who act as "penholder" for Darfur in the Security Council, have proposed a "technical rollover". This would allow the UNAMID mandate to be extended initially without changes.

As a result, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union decided to exclude Sudan. The UN Security Council strongly condemned the violence in a joint press statement. He must decide on June 27 in what form the mandate for UNAMID will be extended. Germany and Great Britain, which act together in the Council as "penholder" for Darfur, introduced the proposal for a "technical rollover" in an open meeting of the Security Council on June 14th. This would allow the UNAMID mandate to be extended initially without changes and to decide again on the further mission of the mission and the progress of the withdrawal in a few months. The Russian representative then accused Berlin and London of "megaphone diplomacy". What is happening in Khartoum is the sovereign affair of Sudan, and since the security situation in Darfur has not changed, there is no reason to slow the transition.

You can see it that way in Moscow. For the UN, it is not just a question of whether power changes and power struggles in Khartoum have a direct impact on the security situation in Darfur. There is also the question of who will assume responsibility for security in Darfur, for development and reconciliation and also for the human rights situation in the future. In the meantime, the UN has rightly stopped handing over locations from which UNAMID blue helmets have already been withdrawn. On May 13, the Military Council announced that these facilities should be handed over to the Rapid Support Forces - the very forces that made it necessary to send the blue helmets 12 years ago.

The United Nations characterize its own approach to ending UNAMID as a "responsible exit". In principle, this is shared by all members of the Security Council. And it can only mean that deduction can be completed and responsibility can only be transferred in Darfur if there is a responsible government in Khartoum.