Imagine a world where your social standing is dictated by a government-controlled formula that constantly monitors and judges your every move and utterance, imposing instant penalties for any perceived misstep. This Orwellian scenario is precisely what's conjured up by the term "Social Credit System." For years, mainstream media in the West has painted a dire picture of China's social credit system, warning of a dystopian future where citizens live in fear of being penalized for their words and actions.

The Social Credit System is a very real policy in China, yet many may not clearly understand its nature and functioning. This article aims to distinguish between reality and misconceptions surrounding the system, clarify its true essence, and assess the level of concern it warrants.

This article presents a thorough and impartial overview, drawing on the expertise of graduates from Germany's esteemed Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). Additionally, it incorporates valuable insights from Vincent Brussee's 2023 publication, "Social Credit: The Warring States of China's Emerging Data Empire," ensuring a well-rounded perspective.

As geopolitical tensions escalate, it's essential to approach the following information with a healthy dose of skepticism. The Chinese government is exerting increased control over the narrative, while Western media outlets often display a strong bias against China. It's crucial to scrutinize all information critically and acknowledge that our understanding is likely limited. That being said, the social credit system is relatively transparent and accessible, unlike China's secretive defense research endeavors. With a development history spanning approximately 25 years, a wealth of information is available for analysis.

Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies

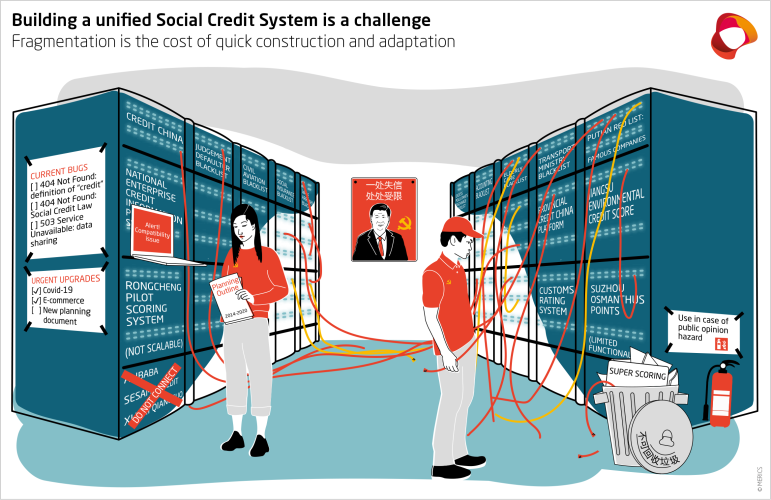

The subject of the social credit system in China is vast and complex. It's also a misnomer because there isn't one integrated system. Instead, it is a general term used to represent a diverse collection of policies and initiatives implemented by various levels of government in China, central and local. Despite this diversity, these initiatives align with their fundamental principles and objectives, which become more apparent when examining the issues the government seeks to address.

From Beijing's perspective, the absence of transparency, ethical standards, and a robust legal framework stifles economic and social growth. A prime illustration of this issue is the frequent disregard for court rulings. Such problems create an unfavorable business environment, as the inability to enforce court decisions renders contracts ineffective. In essence, agreements are reduced to verbal assurances, which can be precarious, particularly for smaller companies entering into contracts with larger, more powerful entities that may exploit their vulnerability.

Beyond these issues, the government acknowledges that inadequate law enforcement has led to a multitude of ongoing concerns, including devastating industrial accidents, breaches of food and medicine safety, bogus financial claims, the proliferation of fake goods, tax avoidance, false insurance claims, academic dishonesty, and other such illicit activities that continue to plague the system despite repeated prohibitions.

The social credit system was launched as a comprehensive solution to address many challenges. As a result, its reach goes beyond the traditional concept of creditworthiness in the marketplace, as seen in other nations. In defining the social credit system, the Chinese government has traditionally employed sweeping and ambiguous language, deliberately avoiding specificity. This approach allows for adaptability in policy-making, which is a top priority.

At first glance, Beijing may seem to be granting itself the unlimited authority to control the Chinese populace, which is a concerning prospect. Yet, surprisingly, the social credit system is quite dispersed and lacks centralized control. Local authorities have been afforded significant autonomy to respond innovatively to Beijing's vague objectives and develop their own unique iterations of the social credit system.

Due to the social credit system's complex and constantly shifting nature, it can be more productive to clarify what it is not rather than attempting to define what it is. A good starting point would be to debunk the prevalent myths surrounding this system and then work backward to better understand its true nature.

One widespread misconception about China's social credit system is that the government assigns a numerical score to every citizen. However, this is not the case. In reality, no centralized scoring system is in place, and most initiatives under the social credit system do not involve numerical ratings. The few that do are limited to experimental programs introduced and managed by local city administrations. These pilot cities played a significant role in shaping the social credit system in the 2010s, with many emerging and disappearing over the past decade.

The initiatives ranged from the ordinary to the foreboding and the bizarre. What they all shared, however, was an air of innovation, as the social credit system remains a developing project with much still to be ironed out. It was the city-based trials that generated the most alarming news stories about China's social credit system, which were then picked up by Western media outlets, perpetuating a sense of unease about China's social credit system.

Rumors have circulated about draconian measures proposed by local authorities to penalize citizens for minor infractions, such as crossing the street illegally, failing to honor reservations at hotels or restaurants, or blasting loud music on public transportation. While most of these harsh initiatives stalled in the planning phase, the few that made it through sent a disturbing message.

The City of Rongcheng in Shandong province stands out as the most egregious violator, exemplifying the most extreme application of the social credit system on record. According to Adam Knight, a PhD candidate at the University of Leiden who researched Rongcheng's social credit initiative, the city's system evaluates businesses, government agencies, and individuals across a staggering 570 criteria, assigning scores that reflect their performance.

People could earn credits for virtuous acts such as donating to charity or giving blood, while they may lose points for negative actions like littering or engaging in public fights. If an individual's rating falls too low, they might face restrictions on purchasing transportation tickets for up to a year. Moreover, they could be publicly exposed and humiliated on a billboard. On the positive side, the initiative led to the dismissal of corrupt local officials and a significant reduction in grievances about misbehaving taxi drivers.

The positive development is that China's state media openly criticized rating systems incorporating punitive measures, such as the one in Rongcheng. The China Youth Daily aptly noted, “People should have rated government employees, and instead, the government has rated the people.” Following this, the central government prohibited scoring systems that penalize individuals. They are now more akin to a loyalty rewards program rather than resembling something from a George Orwell novel.

By 2022, at least 62 cities had implemented their own social credit initiatives. Participation in these programs was optional, and not all utilized rating systems. Residents of these areas must proactively request a government-issued score, as it is not automatically assigned. The incentives offered to high-achieving individuals differ by location, ranging from discounted public transportation fares to priority parking and marginal tax breaks.

On the other hand, having the lowest score in the area would have no significant impact. A more appealing option is to opt out of participating in such initiatives altogether. The latter choice is widely favored in China. Involvement in these programs has been minimal, with many individuals unaware of their existence.

According to a study conducted by Genia Kostka, a professor specializing in Chinese politics at the Freie Universität in Berlin, a mere 7% of participants were aware of a social credit system within their local government. Additionally, the research highlighted that the primary focus of social credit systems in China is on evaluating the creditworthiness of government entities and businesses rather than individual citizens.

Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies

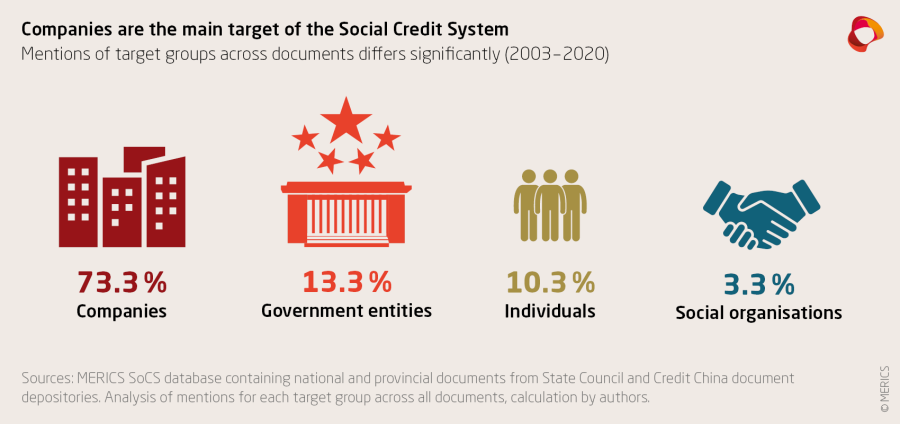

The primary objective of the social credit system is to enhance governance and foster a favorable business climate in China. Consequently, most of the central government's resources have been dedicated to developing the corporate social credit system. This emphasis is evident on the government's Credit China website, which offers a comprehensive overview of the social credit system. The website's content primarily focuses on businesses and public entities, reflecting the system's main priorities. Furthermore, data on enforcement actions undertaken under the social credit system confirms this bias towards corporate entities.

From 2014, when the city pilot programs began, to 2020, 73% of enforcement measures were aimed at businesses. Government agencies were the next most targeted group, accounting for 13% of these actions; 10% focused on individuals, with the remaining percentage focused on non-governmental organizations. While social credit's significance for individuals may increase in the future, its primary focus is on evaluating and impacting private companies rather than personal reputations.

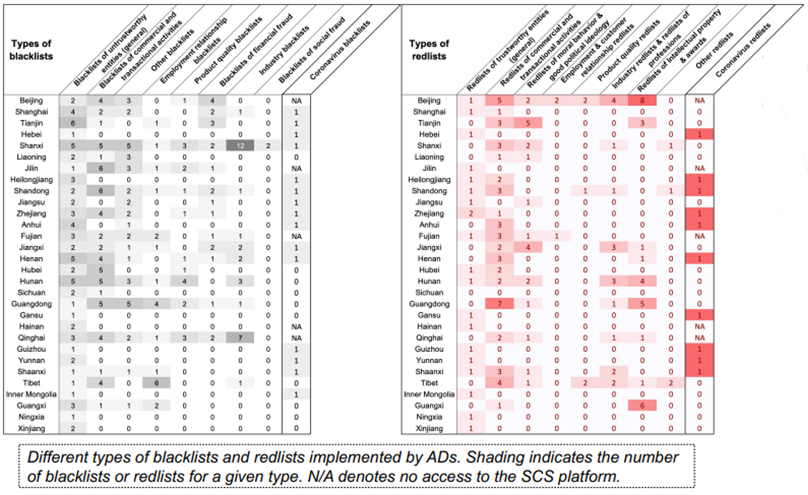

Regardless of their penalty points, individuals and businesses can be subject to government pressure by being placed on a specialized register. This registry, comprised of "blacklists" and "redlists" (the government's term for trusted or "white lists"), plays a crucial role in the social credit system. These two lists are highly fragmented and uncoordinated across central and local governments.

The Supreme People's Court oversees the most influential blacklist on a national scale. This registry documents entities and individuals legally mandated to settle outstanding debts yet deliberately choose not to despite having the financial capability to do so. Before establishing this black list, the court lacked the authority to enforce its decisions, leading to a widespread phenomenon of individuals disregarding its judgments.

Ever since the blacklist was established in 2013, it has evolved into a fundamental component of the social credit system and a valuable instrument for the judiciary. Individuals on the blacklist face limitations on indulging in lavish expenditures, such as purchasing plane and high-speed train tickets, staying at high-end hotels, enrolling in expensive private schools, and acquiring luxury vehicles.

Before inclusion on the list, the court must inform the affected individual or business of its ruling and its justification. Parties that have been blacklisted have the opportunity to have their names stricken from the list and sanctions revoked, provided they consent to settling their outstanding debt and committing to lawful behavior going forward.

In addition to the above, the Civil Aviation Administration and the National Railway Administration maintain no-fly and no-ride lists. These are lists of individuals prohibited from flying or taking the train. Disruptive behavior, such as physically harming transportation employees or fellow travelers, disregarding safety protocols, using counterfeit tickets, or smoking onboard, can land you on one of these lists. As a consequence, you may be barred from purchasing new tickets for a period of six to twelve months. Notably, being placed on this list has no broader implications for your personal or professional life.

Source: AIES Conference

Regardless of one's stance on the infractions and penalties detailed, the centralized government's blacklists appear to possess a certain level of consistency and well-defined boundaries. In contrast, certain pilot cities' ad hoc blacklists lack uniformity and coherence, with no clear-cut parameters or limitations.

Various cities had numerous black and red lists, with their content and emphasis differing significantly from one city to another. To illustrate, in a particular inner Mongolian county, parents who sought to remove their children from local schools teaching Mandarin were allegedly intimidated by the prospect of being placed on a blacklist.

Amid the pandemic, certain cities put citizens on a blacklist for not adhering to mask-wearing regulations in certain urban areas. In Anqing, a resident was even ostracized for allegedly "spreading panic" after sharing footage of an ambulance transporting a person suspected of having contracted the virus. Mainstream Chinese media outlets have denounced these actions, deeming them capricious and unrelated to the principle of "social creditworthiness."

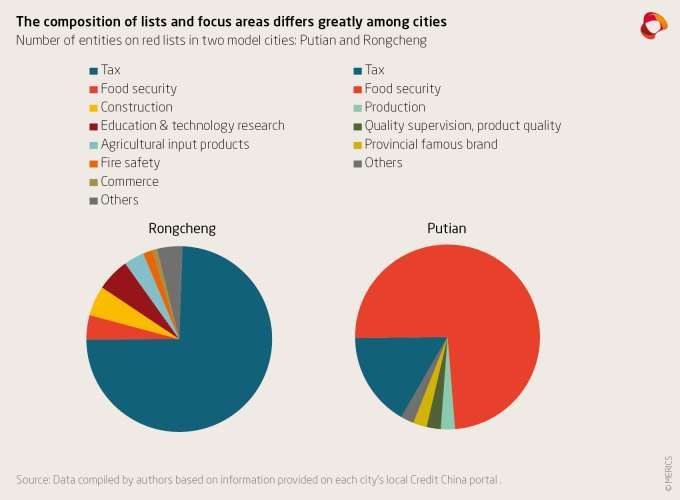

In Zhengzhou, the city authorities indiscriminately red-listed all hospitals handling pandemic victims, commending them for simply fulfilling their obligations. In Rongcheng, 75% of red-listed individuals earned their prestigious status due to their exemplary tax compliance. Similarly, roughly 75% of distinguished entities in Putian were red-listed for meeting food safety standards.

Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies

Beijing seemed dissatisfied with the situation and consequently released a policy document in 2020 aimed at enhancing the standardization of social credit and limiting the abuse of power by local officials. The updated guidelines emphasized that blacklists should be reserved for cases of significant harm, focusing on safeguarding information security and privacy. Additionally, the document underscored the importance of widespread agreement before implementing social credit measures, discouraged the arbitrary creation of new blacklists, and highlighted the need for a transparent process for black-listed entities to restore their credit standing.

One could easily view China's social credit system as an expansion of the surveillance state. The government could monitor and manipulate citizens with precision and ease through algorithms, artificial intelligence, massive data collection, and numerous cameras. This dystopian scenario appears plausible, given the government's penchant for control and access to the technological tools necessary to implement such a system on a massive scale.

Despite the prevailing notion, the facts don't support this assessment. It's striking that a government with extensive surveillance infrastructure relies on an astonishingly rudimentary social credit system, which relies more on antiquated technologies like fax machines and paper-based documentation rather than cutting-edge machine learning applications.

The social credit system's level of digital maturity is evident in official government documents, which repeatedly emphasize the necessity of building comprehensive databases and platforms that facilitate seamless information sharing. A notable challenge, however, is the lack of standardization in data presentation, with cities submitting reports in varying formats, including spreadsheets, news articles, and even JPEG images.

The pilot city initiatives gathered data through manual efforts, utilizing basic tools like Microsoft Excel and WeChat, resulting in inconsistent and uneven data quantities. For instance, in Anqing, a single department was responsible for a staggering 90% of all data accumulated under the social credit system. In contrast, in a metropolis with a population exceeding 9 million, numerous departments contributed a mere trickle of data, with fewer than 100 weekly entries.

The social credit system has taken the concept of big data to a new level, mainly due to the rampant inflation and the motivations of local officials to exaggerate their statistics. Impressive figures can boost a team's reputation and even lead to career advancement. However, a curious phenomenon has been observed: the more data collected, the fewer individuals are actually penalized, suggesting an inverse relationship between the two.

Initial obstacles have hindered the government's efforts to transition to digital systems. This slow progress is attributed to the absence of standard guidelines, a centralized data storage system, ambiguous credit classifications, and disparities in data collection practices across regions and institutions. Consequently, it's unsurprising that the capital has recently prioritized standardization and digitization.

However, suppose you believe this enables them to suppress individuals more effectively. In that case, it is essential to note that the disorganized, chaotic, and outdated execution of the social credit system has led to numerous negative consequences, such as unjust blacklisting of innocent individuals and contentious practices of gathering and evaluating behavioral information in trial cities. In every scenario, the central government in Beijing stepped in to limit the abuses carried out by out-of-control local authorities.

Beijing may not necessarily be portrayed as the positive force in this situation, as we will discuss shortly. However, it appears that the social credit system is becoming a permanent fixture, and streamlining and modernizing its application to eliminate its current chaotic state is not a terrible idea. Furthermore, those concerned about a surveillance state can take comfort in the central government's awareness of the risks of relying solely on automated decision-making processes.

China prioritizes human oversight in its social credit system, as demonstrated by a 2021 amendment to the administrative penalties law emphasizing the need for human review of digitally gathered evidence. Furthermore, as of 2023, most social credit-related decisions were allegedly made by human assessors rather than artificial intelligence.

During a speech in 2018, former US Vice President Mike Pence connected the social credit system to China's surveillance State, describing it as “An Orwellian system premised on controlling virtually every facet of human life.”

In truth, it is a public, somewhat transparent, and diminishing effort to enforce moral standards in the public sphere that is quite separate. While not entirely harmless, it is not as sensational as Pence and others have portrayed. The concept of a social credit score, which is largely exaggerated, has frequently been used to represent a frightening, techno-dystopian future. Over time, it has become a popular cultural reference and the only version of reality that people tend to recall.

It's common to see satirical posts on Chinese social media platforms ridiculing individuals who naively assume that a social credit system is fully operational. On Weibo, for instance, users have created humorous mock-ups of China's social credit app, displaying absurd scores like 726, accompanied by warnings of being under close surveillance as a "second-class citizen" or alarmingly low scores of 0, instructing the individual to surrender, or even a score of -278, demanding immediate execution.

Source: X

Regrettably, the social credit system has garnered excessive attention, overshadowing the fact that China, similar to numerous other governments globally, possesses numerous more effective methods for widespread surveillance, counterinsurgency, countersubversion, political oppression, and social control that often operate covertly and outside the confines of laws and regulations.

While China's social credit system is well-known, fewer people know about initiatives like Project Sharp Eyes, Golden Shield, the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, and Skynet. Unfortunately, freedom and privacy violations occur daily in China and globally, often flying under the radar, maybe because they just aren't as meme-able as the idea of social credit.

It's crucial that we approach all of these issues with a critical eye, accurately identifying and understanding their impact and origins. If we fail to think critically and look beyond the surface level of popular narratives and memes, we risk becoming vulnerable to a surveillance state that erodes our autonomy.

Also published @ Substack.com, BeforeIt’sNews.com, and Steemit.com