The lack of trust in institutions continues to rise worldwide, prompting governments from various countries to up the ante on controlling the flow of information before their citizens lose complete confidence in them. Many governments have proposed regulations over the past two years that would lead to an unprecedented level of online censorship, and some countries have already passed their legislation.

This article focuses on the online censorship bills in Canada, the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States and what effects they may have on the internet, particularly legacy tech and its users.

Canada’s online censorship bill titled Bill C11, also known as the Online Streaming Act, seems to be the most dystopian of all. Bill C11 was first proposed in November 2020 as Bill C10 but failed to pass due to its concerning contents. Bill C10 was reintroduced in February 2022 as Bill C11 and was approved by the Canadian House of Commons, the first of a two-step process to becoming law.

The first approval took many by surprise, including YouTube. YouTube’s concern over the bill compelled them to publish a blog post warning about the Online Streaming Act. As explained in the blog post, Bill C11 would effectively give the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC: A government regulator) the power to decide exactly what content Canadians can see on YouTube and other social media platforms.

Image source: Youtube

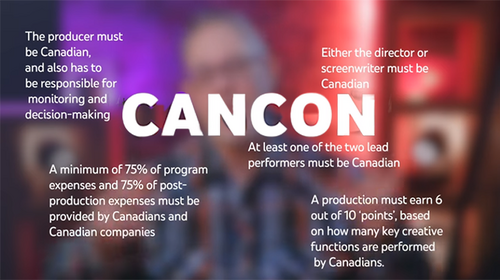

This bill states that these regulations will apply to user-generated content. Besides controlling the amount and type of advertising appearing on YouTubers' videos, the CRTC would have the power to dictate what content they make as per CANCON requirements. They would also be able to label any YouTuber as a so-called broadcaster, which means complying with the CRTC’s criteria or risk being blocked in the country.

Moreover, some broadcasters will also be required to contribute to the Canada Media Fund, which funds mainstream media in Canada. It appears this requirement will only be applied to streaming services and social media platforms, but it could also apply to content creators of other sources. This is significant as most Canadian media is funded directly or indirectly by the Canadian government via the Canada Media Fund. Mandatory contributions by broadcasters would expand the Canada Media Fund, further increasing government control of the media.

Clearly, the Canadian government is desperate to ensure that it continues to control the narrative in the country. This makes sense, considering that trust in the government has been declining for years and exacerbated since the pandemic began. To put things into perspective, 40% of Canadians trusted their government at the beginning of the pandemic. Today this figure stands at 20%, a 50% drop in three years.

The Canadian Senate will vote on Bill C11 in February 2023; if passed, it will go to the Canadian Parliament for debate. Although YouTube presented its case to the senate, it failed to convince the Senate to omit user-generated content from the bill. YouTube expressed that the legislation could set a harmful global precedent for other countries to follow suit. This makes it harder for creators to access international audiences and would impact millions of businesses and the livelihoods of entrepreneurial creators globally.

Image source: Legal 60

In contrast to Canada’s brazen title of Online Streaming Act, the UK politicians chose a more harmless title for their online censorship bill, the Online Safety Bill. The bill was introduced in May 2021 and has been slowly working toward approval since then. Similar to Canada's online streaming act, the UK Online safety Bill initially came under fire for wanting to regulate “legal but harmful content.”

This provision would have been a concern because it would give the UK government the power to censor whatever it deems harmful. In the case of the UK, the regulator overseeing this provision's enforcement is the Office of Communications (Ofcom), which is comparable to Canada's CRTC. Fortunately, the requirement to police legal but harmful content was removed from the Online Safety Bill in November.

Unfortunately, there are other dubious provisions in the bill, which include various requirements that direct Ofcom to protect “content of democratic importance, protect news, publisher content, and protect journalistic content.” Presumably, it means the mainstream media. Moreover, Ofcom still has the power to police illegal content being distributed online and will issue fines to tech companies that fail to police unlawful content. Fines will start at £18 million or 10% of a tech company's annual total revenue, whichever is higher.

The fines would specifically apply when illegal content is shown to children meaning tech companies will be encouraged to do age verification to avoid inadvertently displaying harmful content to minors and then getting fined. This means social media companies will be forced to require KYC from all their users, which isn’t bad relating to scammers and bots. But the trust issues with legacy media and governments weigh heavily in this instance.

Besides, many would argue that it’s up to the parents to take responsibility for what their children see online, not a ruling government body. Furthermore, when you consider the woke society in which some authorities are condoning the content and topics minors are encouraged to see and even participate in is very questionable, to say the least. Also, what’s being taught in schools, specifically relating to gender identity and sexual orientation. We live in a highly polarized society, so who will really benefit from this legislation?

On another note, an ambiguous provision in section 131 of the bill states that Ofcom will have the power to restrict so-called ancillary services, including “services which enable funds to be transferred.” The mind boggles at what this could mean, but hopefully, decentralized cryptocurrency will circumvent this overreach of power.

Trust in the UK government has also plummeted, particularly during the pandemic. With the recent chaos and resignations of four prime ministers in 3 years, one survey shows only 10% trust the government, with 61% polling an emphatic ‘untrustworthy.’ The primary motive for the UK's online censorship efforts appears to stem from a desire for more oversight rather than censorship per se. A significant reduction in government trust has occurred in other countries; however, the motivations for censorship vary.

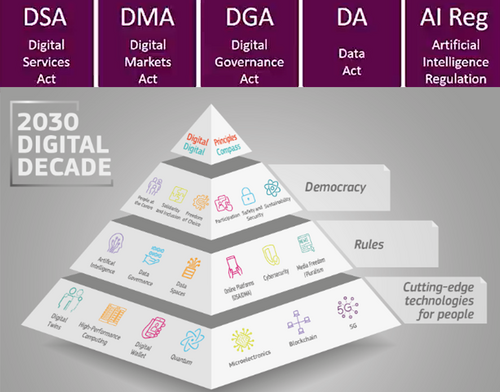

Image source: Digital Strategy Europa

The European Union (EU) consists of several countries. In contrast to Canada and the UK, European authorities separated their online censorship efforts into the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and the Digital Services Act. (DSA) These are two of five bills known as the Digital Services Package, introduced in December 2020 and the second phase of the EU’s 2030 digital agenda. The EU's DMA and DSA were adopted in July and October 2022, respectively, with the new rules to be applied 6 -15 months after their entry into force.

The EU’s Digital Governance Act (DGA) was passed in June 2022 and will fully apply in September 2023. They are also in the process of passing the Data Act (DA), and the takeaway here is the mandatory sharing of data with governments and corporations. The fifth Act is the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Regulation (AI Reg), which could enter into force in early 2023 in a transitional period, and late 2024 is the earliest time the regulation could become applicable. Note that all five bills are regulations, meaning they will override the national laws of EU countries.

The Digital Markets Act has little to do with online censorship, and it could paradoxically make it possible to bypass many of the restrictions that the Digital Services Act seeks to introduce. That’s because the Digital Markets Act would impose massive fines on mega-tech or so-called gatekeepers who maintain their monopolies by giving preference to their products and services. The implications of this are profound and could do severe damage to big tech company profits.

One example is that Apple has a monopoly on its apps for iPhone, meaning all apps must be downloaded from the Apple Store, and some apps can’t be uninstalled. Under the DMA, you can install apps from other stores and uninstall everything from your iPhone. The same would apply to other phones, computers, tablets, etc.

Given that Apple and the like make a lot of money from mining your data with mandatory apps and making developers pay massive fees, the Digital Markets Act could deliver an enormous blow to their bottom line. Big tech companies are not happy and are expected to look for ways to diminish the impact of this Act through court proceedings.

The motivation for the DMA is to increase Europe's competitiveness in the tech space. More importantly, the Digital Markets Act could be a precedent for all sorts of innovation in cryptocurrency in the EU because there would be an entirely new set of hardware available to crypto developers in the region.

The downside of this bill is that it will also require all gatekeepers to provide detailed data about the individuals and institutions purchasing their products and using their services to the EU. This will be facilitated by the Data Governance Act and Data Act which mandate data sharing.

The DSA’s motivating force is to create its interpretation of a safer online environment for digital users and companies. In other words, it will establish a Ministry of Truth in every EU country, censoring certain information and pushing government propaganda. Each country will have the deceptive title “digital services coordinator,” which will function as a Ministry of Truth. Each digital services coordinator will appoint “trusted flaggers” to monitor and take down content. Trusted flaggers will be law enforcement, NGOs, and other unelected institutions.

Regarding the kind of content trusted flaggers would track and take down, the scope seems limited to Illegal content, as in the UK. However, the bill suggests disinformation could be on their radar as well. Now, this begs the question of who defines disinformation and the answer is probably the EU. Violators of the EU's upcoming regulations will face fines of up to 6% of their annual income per infraction, and repeat offenders will be banned. The Digital Services act also contains a provision that could impose KYC on social media platforms, in the name of child safety, like in the UK.

The bill explicitly states that in a crisis, the European Board for Digital Services will instruct social media platforms to enhance content moderation, change their terms and conditions, work closely with trusted flaggers, and tweak the algorithm to “promote trusted information.” In other words, the next time there's a crisis, the government narrative will be promoted, and opposing ideas and positions will be down-ranked or deleted.

Moreover, there's no limit on how long these emergency social media measures would last. As 'they' say, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” Not surprisingly, the World Economic Forum (WEF) is a big fan of the EU's Digital Services Act and claims it will be used as the standard for online censorship worldwide once other countries see its success.

Also, not surprisingly, the WEF has criticized the UK for dropping its ‘legal but harmful speech’ regulation. This further supports the idea that the Digital Services Act will apply not just to explicitly illegal content. The WEF’s article suggests they will also include things like hate speech. It’s inherently a human trait to get emotional with certain occurrences, so if people are angry, why not address the cause rather than censor them; now there’s a thought!

Trust in EU governments fell by almost 25% during the pandemic, and that's the average drop. Many EU countries saw even more significant declines in confidence. The Czech Republic leads the pack, with just 15% of Czechs now trusting their government. It’s evident the EU's totalitarian approach has failed so far.

Whereas the Digital Markets Act was created to make Europe's technology sector more competitive, the Digital Services Act was designed to control European citizens. The last thing the EU wants is for people to lose trust in it, but given the magnitude of these laws will only accelerate that process.

.png)

Image Source: The Heritage Foundation

Similarly to the European Union, the United States has two significant documents related to online censorship. The first bill is titled the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), and the second is a Supreme Court case and pertains to the Section 230 bill. The Kids Online Safety Act was introduced in February last year and is still sitting in Congress but is expected to pass later this year because it has bipartisan support.

However, outside Congress and from both sides of the political spectrum, dozens of civil society groups have criticized the bill. They warned the bill could actually pose further danger to kids by encouraging more data collection on minors in the form of a KYC protocol. It will ultimately force online service providers to collect KYC data to ensure they're not showing harmful content to children.

The provision in the US bill does not explicitly require tech companies to do this, but the bill acknowledges it's the only real option. As in Canada and the UK, a US Government regulator will ultimately decide when kids have been made unsafe online, specifically by the Federal Trade Commission. (FTC) This has also been criticized because it should be the parent's responsibility to watch what their children consume instead of being used as an excuse to monitor and censor everyone else.

What’s more, it's not just the FTC that will be issuing fines. The Kids Online Safety Act will allow parents to sue tech companies if their children have been harmed online. It's assumed social media platforms will turn the censorship up to full throttle to ensure they don't get sued, even with KYC.

The second bill relates to Section 230, in which the Supreme Court will hear two cases about central internet moderation in February 2023. For those unfamiliar, Section 230 is a US law passed in 1996, which allows social media platforms to moderate content to a limited extent without violating the First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech and the press in the United States.

However, big tech has leaned on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act to avoid being held responsible for some of the most controversial content on their platforms. The companies have invoked this federal law to dismiss potentially costly lawsuits in numerous cases.

The Supreme Court case called Gonzalez v. Google alleges that Google supported terrorism with its algorithmic recommendations and contributed to the 2015 terror attacks in Paris, which killed an American student named Nohemi Gonzalez, among many others. It was picked up by the Supreme Court last October after being passed up by various courts of appeal. The same applied to another case called Twitter v. Taamneh, where a Jordanian was killed in a terror attack in Istanbul, and Twitter's algorithms allegedly contributed to the attack.

So, what are the outcomes? If the Supreme Court sides with Gonzales, big tech will be hit with related lawsuits and have to engage in more online censorship to ensure no more cases occur. Notably, this is the outcome the Democrats are pushing for as US President Joe Biden filed a legal brief with the Supreme Court, asking them to increase the liability of social media companies under Section 230. The Department of Justice also filed a legal brief with the same request.

On the other hand, six of the nine Supreme Court Justices were appointed by Republican presidents. Republicans have been calling for Section 230 to be thrown out altogether, arguing that there is too much censorship. Should the Supreme Court decide that Section 230 is unconstitutional, online censorship would instantly become illegal and also apply to algorithms.

Google and Twitter have argued that stripping Section 230 protections for recommendation algorithms would have wide-ranging adverse effects on the internet. Some argue the internet won’t work very well without algorithms. This begs the question, would they be able to remedy the algorithm issues by allowing the user access, with the ability to shape it to their desires? It makes one wonder about the hidden agendas.

Another outcome would be for the Supreme Court to rule in favor of Google and for Congress to amend Section 230. However, allowing Congress to change Section 230 would likely result in even more online censorship. Consider that trust in US institutions has been falling fast and recently hit record lows. Only 27% of Americans have confidence in 14 major American institutions on average, according to a poll conducted by Gallup, which found sharp declines in trust for the three branches of the federal government, the Supreme Court (25%), the presidency (23%) and Congress. (7%)

Image source: Ricochet.com

All is being revealed among centralized entities, governments, and the non-government organization cartels. They are literally turning on each other only to cripple themselves. The Divine end game has been actioned and is very positive for decentralized media platforms. Billionaires are flipping, and technology has made it possible to disseminate critical information that uncovers secrets and lies that have enslaved us, is now prolific. No centralized entity of a few can control the masses if we don’t let them. Free speech will find a way.

And be mindful that in this world,

“The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Truth with lies, the Ministry of Love with torture, and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation. These contradictions are not accidental, nor do they result from ordinary hypocrisy: they are deliberate exercises in doublethink. For it is only by reconciling contradictions that power can be retained indefinitely. In no other way could the ancient cycle be broken. If human equality is to be forever averted—if the High, as we have called them, are to keep their places permanently—then the prevailing mental condition must be controlled insanity. — Part II, Chapter IX 1984

(19).gif)

Also published @ BeforeIt’sNews.com; Steemit.com; Substack.com