In a post about entrepreneurship education, Gary Schoeniger, chief content development officer at the Entrepreneurial Learning Initiative, argued that entrepreneurship isn't really about acquiring business skills such as spreadsheets and marketing plans. Instead, entrepreneurship is the way someone thinks.

Business skills, Schoeniger continued, somewhat controversially, may, in fact, get in the way of entrepreneurial thinking. Teaching business plans and financial projections "may be doing more harm than good.

"While these skills may be important for managing an existing business with a proven product or service," Schoeniger wrote, "they often inhibit the entrepreneurial process -- the process of searching for a problem-solution fit."

As someone who ran an international organization that has taught entrepreneurship to more than, young people, I see his point. The confusion between running a business and being an entrepreneur is real and does a disservice to both skill sets. While business skills are certainly helpful tools, they are different from what the focus of entrepreneurship should be.

In short, while skill, experience, knowledge and passion help you run your business -- or someone else's -- they are management endeavors; and of course they are to be appreciated for the challenges they present.

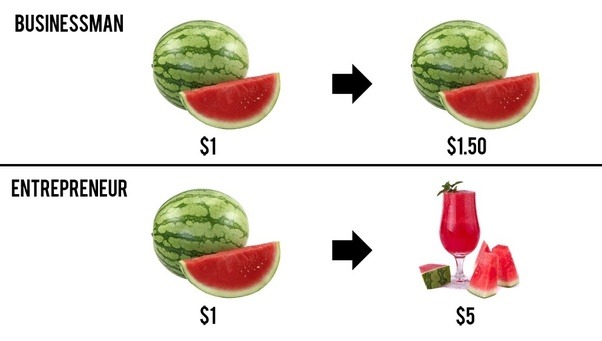

But look at risk as an example of the entrepreneurship-management divide: Many business schools and programs teach tactics for managing and mitigating risk. In business, risk is to be avoided, hunted down and quashed. Investors, managers, executives and employees all fear risk. And with good reason.

To an entrepreneur, however, risk is the lifeblood of success. Innovation and creation aren’t possible without it. Entrepreneurs taught this concept correctly learn to evaluate and embrace risk. In contrast, every time that someone learns "risk avoidance" as a supposedly legitimate business skill -- well, that’s flatly un-entrepreneurial.

There are other examples of cases where business-management skills and entrepreneurial thinking part ways. Collaboration is one. Business leaders tend to guard innovation while entrepreneurs want to share and exchange ideas, even with potential rivals.

“Most business owners and entrepreneurs are not aware of the distinction in skill set between those who can successfully run a business and those who are true entrepreneurs,” David Litt, founder and CEO of Blue Star Tech, said , addressing this distinction. Litt knows what he's talking about; he's run multiple companies. “The difference is somewhat like being ambidextrous," Litt said. "Most people are right- or lefthanded, but very few people use both hands similarly.”

Entrepreneurship, then, isn’t a "job"; it’s a way of thinking about and approaching challenges and opportunities. That's why real entrepreneurs flourish in government, non-profit organizations and business -- as both employees and founders. It’s well established that the entrepreneurial mindset makes for outstanding employees because they identify problems early, and present solutions. Entrepreneurship-employees take ownership of their jobs and performance and tend to both think creatively and collaborate well.

Whatever industry they choose, entrepreneurs should be the ones running existing companies, starting new ones and thinking big, “holy cow”-type thoughts. We need more of them, taking risks and solving problems.

Today's economy is both global and fluid -- more so than it’s ever been. Entrepreneurs, maybe more than businesspeople with any other skill set, are the best choice to embrace and lead the world we have now and the one we will have soon.

If it were up to me, we’d start teaching entrepreneurial thinking as early as middle school, maybe even earlier. And, just as important, we’d look at entrepreneurship and business as related, but different, skills.

"Entrepreneurship education" teaches you that you can own your future, not just your own business. That's an important distinction.